Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Currencies myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Ruurd Brouwer is the chief executive of TCX, and Barry Eichengreen is professor of economics and political science at the University of California, Berkeley.

The relation between banker and borrower is tricky. They need each other but have opposing interests and different levels of expertise. Because banks are financially more sophisticated than households, governments adopt consumer-protection laws to safeguard their interests. But not all borrowers are protected.

A soon-to-be-published IMF survey of national debt management offices in emerging and developing economies shows that such knowledge asymmetries are not limited to commercial banks and domestic borrowers.

The grim reality is that in many cases DMOs still lack the training and knowledge to understand even the pretty basic risks of borrowing in foreign, hard currency — the classic “original sin” of emerging markets.

According to the IMF survey, half of responding DMOs don’t perform stress tests on the local currency value of the debt stock, nor on interest payments and amortisation payments. Fewer than half had a currency risk management strategy, and only a third had senior staff dedicated to the risk management of the sovereign debt book.

In effect, poor countries are driving their “debt mobile” at 100mph in the dark with no headlights, and no map. Blindfolded.

The IMF has found that this unattended currency risk leads directly to accidents. A study of 222 debt surges in developing countries over the past 50 years found that currency risk alone caused debt/GDP ratios in low-income countries shoot up 35-50 percentage points during crises.

That’s like Germany’s debt-to-GDP going from 60 per cent to 110 per cent in one year. Such an increase would push a developing country immediately into high risk of default, or straight into default itself. And that’s exactly what’s happening today in some countries.

About 90 per cent of respondents to the survey indicated further that it was important to pursue capacity development in areas like risk quantification, the use of derivates and local capital market development. This meshes with this year’s World Bank International Debt Report, which has smart advice to DMOs in low and middle income countries:

Once a portfolio analysis is conducted, debt managers can employ an active debt management strategy — including repurchases, swaps, and cancellations. If done correctly, such a strategy can optimize the profile of the public debt and achieve considerable financial gains.

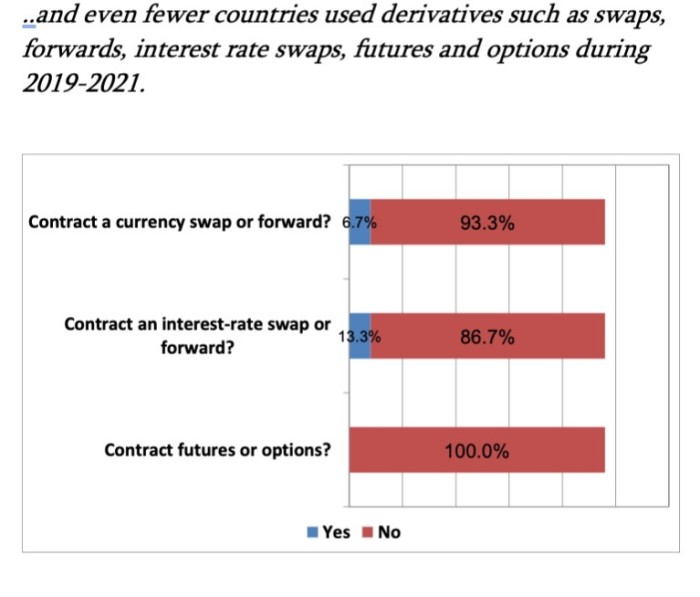

Unfortunately, techniques that were rightfully placed under the heading of innovative practices are, in reality, at a very different state of advancement, according to the IMF survey . . .

All this shows the painful knowledge asymmetry at the debt negotiation table: on one side are borrowers with limited knowledge of currency risk management, while on the other the World Bank and the IMF that are full of financially-savvy employees (and banks and bond funds have hordes of them).

Defenders of the multilateral development banks will respond that the World Bank and other MDBs — unlike commercial lenders — are not return maximisers. But does this mean that their clients are protected from taking on excessive risk?

Well . . . no. The development banks are risk minimisers, mandated to protect their AAA rating. Offloading currency risk is as natural for a development banker as maximising return is for a commercial banker.

Maybe we should look to lessons from central and eastern Europe, where millions of consumers succumbed to a similar ‘exchange rate illusion’ before the 2008 financial crisis. Attracted by low interest rates they chose Swiss franc mortgages, ignoring the risk of currency depreciation until it happened.

At this point, however, consumer protection provisions kicked in. The European Central Bank highlighted the “malign riskiness of foreign currency loans”, and the European Financial Stability Board warned of the systemic risks that it entailed, and issued the following recommendation on lending in foreign currencies to its member countries:

— Require financial institutions to provide borrowers with adequate information regarding the risks involved in foreign currency lending (…).

— Encourage financial institutions to offer customers domestic currency loans for the same purposes as foreign currency loans as well as financial instruments to hedge against foreign exchange risk.

The European Union’s Mortgage Credit Directive formalised the EU’s position that borrowers should have the right to convert loans to the currency in which the borrower receives their income, or that there are other arrangements to limit currency risk in place.

At the request of the European parliament’s Committee of Economic and Monetary Affairs, the Policy Department issued advice on the mis-selling of foreign currency mortgages — defined as “practices that are detrimental to customers, with or without illegal behaviour”.

There’s a direct analogy here. The three recommendations to protect clients from mis-selling foreign currency loans should be equally applicable to today’s sovereign debt crisis: there should be social policy measures aimed at covering the losses of the most vulnerable customers.

Heavily-indebted low-income countries should also be provided with “accessible and effective out-of-court dispute resolution mechanisms”. Their absence is a painful reminder of the G20’s Common Framework’s ineffectiveness. As in the case of foreign currency mortgages, “the costs of mis-selling must be borne by the institutions that caused it.”