Receive free Markets updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Markets news every morning.

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Stocks falling for two weeks straight. Bonds too. Is it the end of the world, or is it just August? Some of both? Email us: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

Bonds

Everywhere you look, long bond yields are busting out. The 10-year yield is at its highest since 2007; the 30-year since 2011; and the 10-year inflation-protected yield, since 2009.

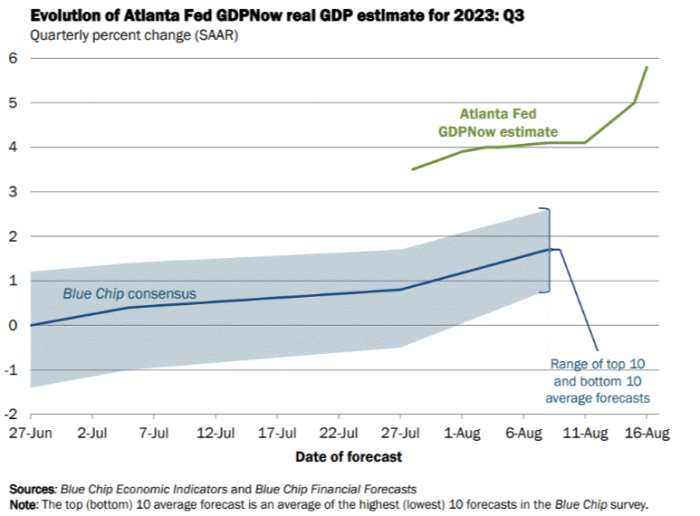

There is a simple explanation. Growth appears to be re-accelerating. After this week’s strong retail sales and industrial production reports, the Atlanta Fed’s third-quarter GDPNow projection is at a staggering 5.8 per cent:

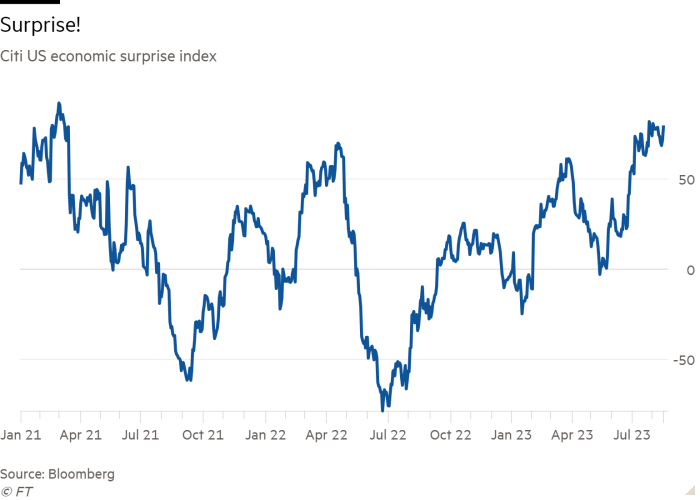

This is misleadingly strong, and is very likely to fall as the quarter progresses. But the trajectory of recent economic data cannot be ignored. The economy is simply hotter than most investors expected. The Citi US economic surprise index, which rises when data comes in stronger than consensus expectations, is at its highest point since early 2021:

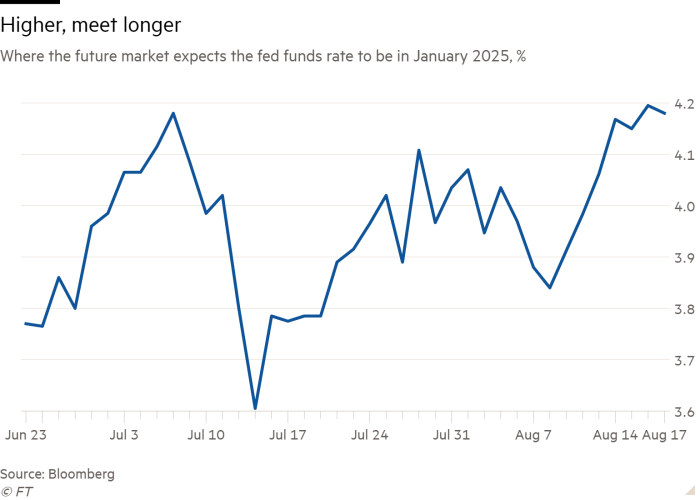

A stronger economy, and the concomitant risk of a second inflation wave, means interest rates may well stay higher for longer, and so markets are revising their expectations. Here is the futures market’s expectations for the fed funds rate in early 2025:

Behind the simple higher-for-longer story, there is another debate among rate watchers: do long bonds face a net supply glut?

“Gluttists” point to other recent bond-market news to explain sagging US long bonds. These include Fitch’s US debt downgrade (which flagged long-term fiscal problems which could lead to investors demanding higher Treasury yields), the Bank of Japan’s yield curve control fiddle (which lowers Treasury demand by raising attractiveness of local debt for Japanese investors) and a surge of long-dated Treasury issuance (raising supply).

“The omens for government bonds do not look great,” Michael Howell of CrossBorder Capital wrote in a recent note. “Even if policy interest rates stay where they are and assuming inflation subsides, US 10-year Treasuries could test 5 per cent yields before they re-test 3.5 per cent yields. The problem is the net supply of longer-term coupon-paying bonds.”

Taking the other side, Ryan Swift, US bond strategist at BCA Research, told us these are firmly secondary to what’s happening to growth. Stories about Treasury supply are part of the “list of reasons you pull out to be bearish” on bonds, but the future path of policy rates is what matters. He is joined by Dave Rosenberg of Rosenberg Research, who wrote yesterday:

Our work has shown that the impact of supply on yields is very weak. The tightest correlations are with the expected direction of Fed policy and inflation, headline and core. Fiscal policy doesn’t factor in that much, actually. Look at the historical record. The United States recorded its largest budgetary surpluses in 1999 ($126bn) and 2000 ($236bn) and the yield on the 10-year T-note rose over 40 basis points through those two years.

Underlying this disagreement is a question we discussed on Monday: is regime change under way in Treasuries? An end to 40 years of falling interest rates, more volatile inflation and historically large peacetime fiscal deficits raise the spectre that bonds are no longer the “safe” asset class. Or, perhaps, the anomalous low-rate environment is simply ending, and bonds, while they won’t deliver huge capital gains anymore, can go back to their old role as cyclical portfolio diversifier.

We put this to Roger Aliaga-Diaz, head of portfolio construction at Vanguard. He thinks that fiscal and other inflationary pressures may already be baked into the neutral rate, the interest rate that keeps the economy in equilibrium:

Fiscal sustainability concerns and inflationary pressures from ageing effects on social insurance programs are all incorporated into higher [neutral rate] estimates. These are drawn-out long-term processes that shouldn’t have immediate effects on long yields. My point is that perhaps the bond market has already adjusted to this higher [neutral rate] reality, with the 10-year yield likely to stay in the current 4%+ range.

As a result, Aliaga-Diaz says, long bonds will provide a good diversifier in case of a recessions, which cash will not.

We suspect greater Treasury supply is not fully priced in, because markets have little experience with deficits at today’s levels. But as Aliaga-Diaz says, these are slow-building pressures, and may outlive whatever is left of this cycle. (Ethan Wu)

A case for Amazon

A few weeks ago, I wrote that I liked the prospects for Apple’s stock more than Amazon’s. To oversimplify, I argued that Amazon is priced for growth yet its growth is slowing, even as the market may be becoming more hostile to growth stocks. Apple, while no cheap stock, prices in modest revenue growth expectations and throws off gobs of free cash flow.

Michael Taylor, who manages portfolios of growth stocks at Baillie Gifford in Edinburgh, called me up to make the case that Amazon’s can grow robustly, even off a half-billion-dollar revenue base. He made four points:

-

The slowdown in growth in the Web Services business is cyclical, not secular. In just a year, growth at AWS has fallen from more than 30 per cent to 12 per cent in the most recent quarter. But the business is designed to be cyclical: clients can rent more or less computing capacity from AWS as their needs rise and fall — that’s what makes the product such a good deal. The tech industry is undergoing post-pandemic contraction, and that is showing up in AWS’s results. But this is not permanent (when I look at the data, to be honest, I can’t tell if the decline is secular or not).

-

The US online retail business is under-earning because it over-invested during the pandemic. When online demand went wild in the pandemic, Amazon spent heavily in warehouses and logistics centres. Now that demand has tapered off, the extra capacity is depressing margins. But warehouses don’t go out of date. Amazon will grow into its infrastructure footprint and margins will expand. This is already starting to happen.

-

There is long-term margin expansion potential in US online retail. Not only is the US market underpenetrated online compared to other global markets, but the US retail revenue reporting line includes Amazon’s “other” businesses — various experiments and longshots. Over time, as these bets either come to fruition or are dumped, margins in the mid to high single digits (roughly what a high-quality bricks-and-mortar retailer earns) will shine through.

-

Advertising is a big, fast-growing, high-margin, unappreciated business for Amazon — a $40bn-a-year business already, and it’s growing at a 20 per cent clip.

Taylor points out that the Wall Street consensus expectation is for Amazon to produce $66bn in free cash flow in 2025. That’s a 4.7 per cent free cash flow yield, which does not speak to an insane valuation. And Taylor thinks that if things go well the number could be closer to $100bn.

I find this argument pretty compelling. What I worry about is that Amazon is not very interested in being a profitable company. It will always prize growth over profit; company’s customer-focused mission encodes this.

I put this worry to Taylor. He cited the high margins in the AWS division as evidence that Amazon is not in principle averse to high margins. And he said that even if the company is reinvesting every dollar it generates, he doesn’t mind, so long as the investment shows strong incremental returns. Fair enough, but there is no guarantee, for any company, that there is always another non-dilutive investment opportunity. That’s why Apple, wisely, devotes so much capital to dividends and buybacks.

One good read

Some welcome AI scepticism from John Thornhill.

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, hosted by Ethan Wu and Katie Martin, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.