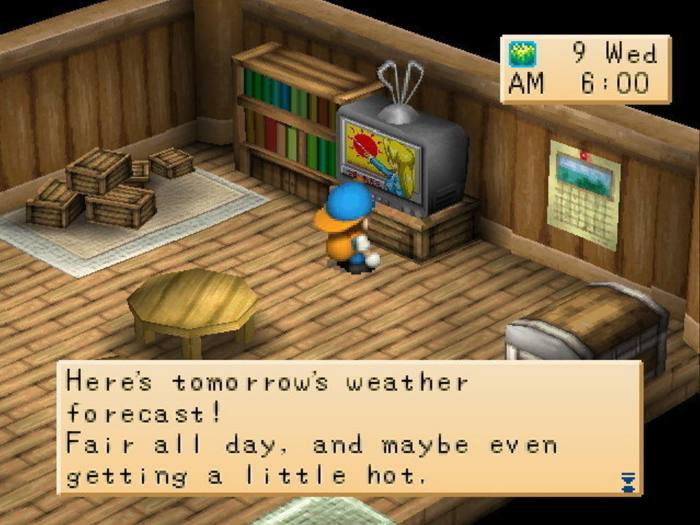

One of my most precious childhood heirlooms is a yellowing scrap of paper on which is written a schedule. “6 AM: wake up. collect eggs” it reads, in the careful joined-up handwriting I used at eight years old. “6.20: water parsnips (unless raining).” My younger brother and I created this routine to help us run our farm in the 1999 PlayStation game Harvest Moon: Back to Nature. We whiled away many a happy hour tending to our modest patch of virtual land.

Today, two decades on, we’re at it again. We’ve spent more than 60 hours farming in Stardew Valley this year. These days our approach differs, though. We dispatch the daily chores with maximum efficiency, tilling vast tracts of land and planting only the most profitable crops. A decade of adult life in London has turned our farmer avatars from utopian homesteaders to hard-nosed agribusiness tycoons.

Of all the curious trends in gaming, the enormous popularity of farming simulators is one of the strangest. Since the original Harvest Moon was released in 1996, the genre has steadily grown, peaking with 2016’s Stardew Valley, which has sold 20mn copies despite being largely made by a single developer. Over the past year we’ve seen fresh variations on the farming genre that include vampires, witchcraft and robots. Why do so many gamers choose to spend their leisure time not shooting baddies but ploughing fields?

At the outset of every Stardew Valley day, I feed the animals while my brother waters the plants. These bitesized tasks are easy to achieve, providing steady doses of satisfaction as you tick them off the list. While many games only allow you to interact with their world through violence, pacifist farming sims are a key constituent in the growing stable of “wholesome games”. They encourage a slower pace of play, eschewing competition and tension. Rather than targeting the brain’s fight or flight mechanism, they invoke the gentler motivations of “tend and befriend”.

Generally these games don’t just offer a job, they provide a whole vibe. Live a while in a pastoral idyll where the light is forever honeyed and each fruit from the orchard is perfectly plump. Beyond the daily chores of the farm, you can engage in activities such as mining, cooking, fishing, socialising with locals and occasionally some light dungeon-crawling. You are encouraged to decorate your home with new furniture and landscape your farmland. Express yourself creatively across your own little patch of heaven — this is the promise that made pandemic hit Animal Crossing: New Horizons one of the bestselling games of all time.

This opportunity for creative control has been cited by real-life farmers as one of the reasons they play the ultra-realistic Farming Simulator series, whose latest edition introduced crops such as grapes, olives and sorghum. Here you don’t simply press A to harvest, but must instead source the right parts for your plough and cultivate the land inch by painstaking inch. The game is so popular that some online streamers make their living from viewers’ donations for tending virtual fields, and the annual esports league offers a prize of €100,000 — more than many real farmers make in a year. Even Angela Merkel has been spotted playing it.

There is a dark side to the genre. Stardew Valley starts as the tale of a protagonist who leaves their corporate city job to take over a disused family farm, seeking a slower life and to reconnect with nature. Yet as you play, new features and objectives encourage you to pursue automation and maximise profits — not to bond with the landscape, but to subjugate it. This view recalls the vacuous FarmVille, a popular game originally released in 2009 which offered mindless and addictive gameplay but achieved massive success. Earlier this year its creator Zynga was bought by gaming behemoth Take-Two Interactive for $12.7bn.

All farming sims, even the most cynical, peddle the same fantasy, and that dream of returning to the land is nothing new, stretching back at least as far as Thoreau’s Walden in the mid-19th century. Some may dismiss it as a nostalgic fantasy of an idealised past, but perhaps it is a necessary act of self-care. In the light of the climate crisis it’s understandable that younger players might seek in their digital media a relationship with the earth which is healing and reciprocal rather than extractive.

Virtual farms may not show the reality of modern agriculture, of automated milking and battery-farmed hens, but at least they demonstrate that gaming can reward players for being kind and nurturing, rather than dominant and vengeful. In my family, at least, they have provided an opportunity for low-impact sibling bonding over decades. No matter where we are in our lives, we can sit down and take simple pleasure in sowing our cauliflower and strawberry seeds in time for the spring rains.