This article is an onsite version of our Moral Money newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered three times a week. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters.

Visit our Moral Money hub for all the latest ESG news, opinion and analysis from around the FT

Welcome back. Yesterday, Russian gas giant Gazprom reported its biggest loss in at least a quarter of a century, after a plunge in sales to Europe.

But other parts of the fossil fuel industry continue to boom — not least the coal sector, with backing from some of the world’s biggest banks, as I report below.

Also today, Lee asks whether better days could be in store for the lacklustre market in sustainability-linked bonds, a seductive concept that has so far failed to gain real traction.

Have a great weekend. — Simon Mundy

FOSSIL FUEL FUNDING

No lack of friendly bankers for coal companies

At a G7 meeting in Italy this week, ministers from the biggest developed economies published an eye-catching pledge to “phase out” coal power. But there are caveats.

The pledge applies only to “unabated” coal power — that is, plants that don’t capture any of their emissions. There is flexibility on timing too: the G7 has promised to do this phaseout in the first half of the 2030s “or in a timeline consistent with keeping a limit of 1.5C temperature rise within reach”, leaving scope for wrangling over what exactly the latter means.

And, of course, the world’s biggest sources of coal demand growth — Asian economies including China and India — are not G7 members, and show no sign of falling in line with its agenda on coal.

So coal’s demise looks very distant indeed — as a new piece of research makes glaringly clear.

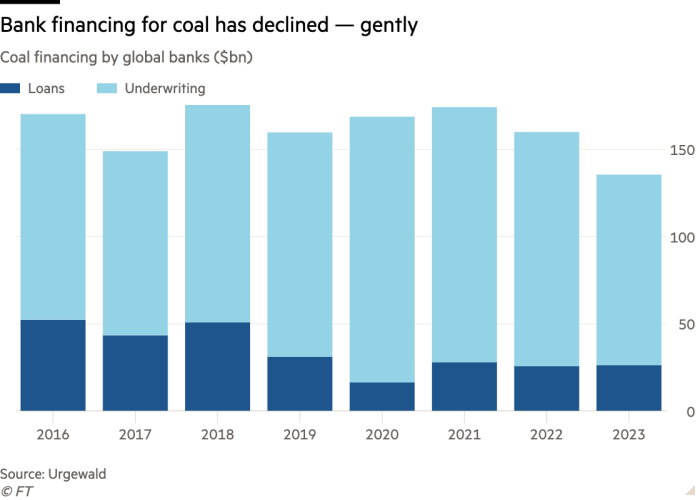

The report, published yesterday by Germany-based Urgewald in partnership with other non-profit groups, tracked banks’ financing for coal companies from 2016 to 2023.

The data includes both loans and underwriting work, and covers all financing for companies that are on Urgewald’s Coal Exit List. Some companies that make the list are expanding coal production or infrastructure. Also included are companies where coal provides a large proportion of revenue or power production, or that have a large amount of coal production or coal-fired generation in absolute terms. The financing figures reflect how big coal is as a part of these companies’ business.

“The best-in-class banks,” said Urgewald director Heffa Schücking, “are those that don’t turn up in our research” because they do not work with coal companies.

Among the major coal company financiers that do turn up in the Urgewald research, there are striking differences in terms of the direction they’ve taken since the 2015 Paris agreement.

Some of the biggest coal financiers have cut down over the past eight years. JPMorgan Chase was the third-biggest US bank financier for coal businesses last year, with total financing of $1.8bn, according to Urgewald — but this was down 38 per cent from the 2016 figure. Citigroup’s figure of $1.6bn was down 50 per cent from 2016.

Europe’s biggest coal financier last year was Barclays at $1.4bn, although this was a 32 per cent decline from 2016. Japan’s biggest coal financiers, led by Mizuho Financial Group at $2.3bn, mostly showed significant double-digit percentage declines from 2016 to 2023 (Mizuho was still the world’s biggest provider of bank loans to the coal industry over the past three years, according to the report).

India’s biggest coal financiers including State Bank of India have also shown big declines in this sort of work since 2016 — although they are likely to change course after the government announced plans for a big expansion of coal capacity in the coming years.

These reductions reflect an overall decline in bank coal financing, which fell to roughly $136bn in 2023 among the 638 banks in this study — 20 per cent lower than in 2016.

If that decline looks relatively modest, it’s because some banks have been increasing their coal financing in a big way. Bank of America is now the biggest US bank backer of coal, according to this report, with total financing of $2.8bn last year, up 30 per cent since 2016. In a statement, Bank of America told me it had reduced exposure to the thermal coal mining sector — one part of its overall coal exposure — by 94 per cent since 2019, and was “on a trajectory to phase out such financing by 2025”.

Bank of America only narrowly beat Jefferies, which previously had little coal exposure but has now become a major partner of coal-heavy businesses including India’s Adani Group (most of last year’s figure came from a major investment in Adani companies by US investment firm GQG Partners, brokered by Jefferies).

By far the biggest coal financiers, however, are in China, which accounts for all of the top 20 spots in Urgewald’s table of underwriters to the coal industry, led by state conglomerate Citic.

Overall, Chinese bank coal financing declined 13 per cent from 2016 to 2023. But a report last month from Global Energy Monitor made clear that the coal industry in China and globally remains in rude health. Last year, global coal power capacity rose by 48 gigawatts, or 2 per cent, with China accounting for two-thirds of that growth.

For all the strong words from rich-world governments this week, they’re only nibbling at the edges of the world’s coal problem. (Simon Mundy)

green finance

Are sustainability-linked bonds getting serious?

In the topsy-turvy world of sustainably labelled debt, green finance wonks are feeling upbeat after a major polluter missed a climate target.

Italian energy company Enel is the world’s largest issuer of sustainability-linked bonds, which penalise companies with higher interest rates if they miss climate targets. On April 23, Enel announced that it had failed to meet a 2023 goal to cut emissions by more than a third, compared with 2022. This triggered a step-up on the coupon for Enel bonds worth about $11bn.

Bondholders will now receive millions of euros in additional interest payments, largely as a result of Enel’s failure to decommission coal power plants on schedule.

Far from seeing the event as a knock to SLBs, however, analysts hope that the penalty could restore confidence in a market that has been struggling to take off.

“The fact that the target was missed demonstrates that it was ambitious in the first place,” Sustainable Fitch, a sister company of the Fitch credit rating agency, said in a report. Jo Richardson, head of research at the non-profit Anthropocene Fixed Income Institute, called it a “coming-of-age moment”.

Unlike green bond proceeds, which are restricted to a specific use, SLBs focus on outcomes, allowing companies to decide how best to deploy the funds as long as they hit their sustainability objectives.

“We don’t need to know if they will use more solar panels, or employ more skilled workers to develop better products — it’s up to the company,” Katsiaryna Souvandjiev, ESG lead at Austria’s Raiffeisen Bank International, told me.

SLBs enjoyed a rapid run that peaked in 2021, but issuance has since fallen off. Some critics have said that borrowers set easy targets, while others argued that the step-up embedded in the bond’s terms was not substantial enough to spur greener behaviour. The decline in SLB issuance accelerated in the first quarter of this year, dropping 34 per cent from the same period last year, according to the Association for Financial Markets in Europe.

Enel said that it failed to hit its objectives because the Ukraine war squeezed gas supplies, and the national grid operator required the company to maximise its coal-fired power plant production.

Following the news of the step-up, Enel’s SLBs rallied, outperforming its so-called “vanilla” bonds not linked to sustainability targets. That makes sense, since the SLBs will now pay out a higher coupon.

But markets were surprisingly slow on the uptake. Enel’s sustainability reporting had suggested that it would probably miss its emissions target for 2023, and watchdogs such as the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis had drawn attention to its likely underperformance.

It’s not the only time bond markets have proved slow to react to new information on corporate emissions. Take London & Quadrant Housing Trust, a UK-based residential developer and housing association, that issued a £300mn ($340mn) SLB in January 2022.

L&Q announced in March that it would probably miss a target to reduce emissions from its own operations and from the energy it uses. (It blamed the rising cost of renewable energy.) Failure would trigger a 12.5 basis point step-up on the bond, to be paid for more than seven years. Yet, as Richardson observed in a recent note, the pricing of L&Q’s SLB hardly budged in relation to a longer-dated vanilla bond.

If Enel’s step-up shows that at least some issuers are setting meaningful targets, it remains unclear whether the increased interest rate will be painful enough to shape the company’s capital allocation.

The step-up will probably force Enel to pay about $90mn more in interest payments, according to a calculation by Bloomberg Intelligence. Last year, Enel’s net interest expense was €2.9bn ($3.1bn), on operating income of €12.8bn. So while the SLB interest hit won’t break the bank, Richardson said that the event could impact Enel’s strategic planning by putting decarbonisation front and centre.

“You’ve got sustainability teams speaking to the CEO, the CFO, the board. It’s a significant event, and part of the investor dialogue, almost irrespective of the financial cost,” she said. Plus, she added, “infrastructure projects being funded with these bonds care a lot about marginal costs.”

One potentially positive harbinger is Public Power Corporation, Greece’s state-backed utility, which issued SLBs in 2021 that drew attention as Europe’s first sustainability-linked junk bond. (PPC was at the time rated BB- by Fitch.)

In 2022, PPC missed a sustainability target for one of its SLBs, triggering a 50 basis point step-up. But after a delay, last year it retired 0.5GW of coal-generation capacity, likely putting it back on track to meet its 2023 sustainability target.

The record of SLBs at utilities could see them more aggressively deployed in sectors requiring transition finance, some analysts said.

“For certain industries, a sustainability-linked product will be the only type you can get,” Anna Crosby, a partner at law firm Fieldfisher specialising in energy and asset finance, said. In oil and gas, she predicted, “that’s how banks will be able to justify investment”. (Lee Harris)

Smart read

To understand BHP’s attempted takeover of mining rival Anglo American, look to the surging demand for copper driven in large part by the energy transition, writes the FT editorial board.