Below the hulking rocky mass of the Devil’s Point, a group of young women approach a small mountain shelter on a rainy late-summer day. Grey skies bear down. Having traipsed across the Lairig Ghru mountain pass, they are grateful to reach Corrour, a simple bothy beside a stream, surrounded by the peaks of the Cairngorms. There are six of them in the party, determined and ambitious, I imagine, as they are old North London Collegiate girls, now training at other educational establishments. It’s September 1, 1939. They have heard disquieting rumours on the journey, and war threatens, but for now, they continue to enjoy their escape into the mountains.

My journey to Corrour with my friend Alison is under happier circumstances and sunnier skies. Escaping only everyday life, we set off from the Linn of Dee car park, about six miles west of Braemar, in midsummer heat. It’s 4pm but the light has the never-ending clarity of Scottish summer. I am in the middle of researching a book about bothies — mountain shelters, freely available for any passer-by. There are about 100 of them in Scotland, plus a few in England and Wales, but a visit to Corrour, one of the oldest still in use, feels like a pilgrimage.

Named after the corrie behind, Coire Odhar or “the dun-coloured corrie”, it was built in 1877 as a temporary home for the man who counted deer and chased poachers from the estate. But the hut fell out of use, the last watcher leaving in 1920, and soon it was instead housing hikers.

Alison and I hoist bags on to our backs, slather on sun cream and start the long walk to Corrour, first along the boring, dusty Land Rover track to Derry Lodge, then winding our way higher across the Luibeg burn and into the hills. Countless others have trudged this way, hoping to bag peaks such as Ben Macdui, supposedly haunted by the fearsome “Grey Man”. We follow their path; our steps fall in line with companions who came before us. We are connected by the tread of our feet, the movement of our bodies, the patter of our voices.

There are other traces of earlier visitors too. Before going on this trip, I spent happy hours in archives in Dundee and Perth reading the old visitor books that were left in bothies almost from the start. The “bothy books” are full of tales of adventure and friendship, songs, feats of derring-do, drawings, and jokes. As a historian, I was immediately drawn to these records of ordinary people in particular places. In the very first Corrour book, from 1928, one visitor quotes Psalm 121: “I to the hills would lift mine eyes.” Just as Alison and I do, he delights in his journey, marvelling at the mountains. Or he would if the “bloody mist would rise”. It does not, he adds, oblige.

It’s easy to see why Corrour has been a meeting point for many seeking shelter. Bothies are a safe place from the elements, from wind and weather. But more than physical refuge, bothies are a respite from life’s grinding rhythms, stress, and work. I began going to bothies at the same time as I was leaving a hectic London life that had worn me down and escaping a difficult relationship that left scars. The transitory space of the bothy provided freedom, and somehow, I felt I was not alone.

A few pages into Corrour’s first book, in August 1928, DE Strand from London scribbled a slight misquote of “The Last Journey”, a poem by John Davidson: “alone I climb / The rugged paths that lead me out of time”. In a bothy, time seems suspended for a moment. You occupy a limbo that provides relief from the worries and strife of the world beyond the bothy door.

Corrour’s roots lie in the particular freedom of the interwar years when hiking exploded, and young men and women, many working-class, indulged in “knapsackery” in the mountains. In that golden but poignant moment of peace in the 1920s and 1930s, there was time for carefree camaraderie and venturing outdoors. Adventures for men such as Archie Hunter, from Drumoyne, Glasgow, who first visited Corrour on his 21st birthday in 1930. He’s a slightly difficult character, dismissive of women and prone to pretentious musings about rough granite, skies and providence. But I understood that he wanted to flee to a wild world away from industrial Drumoyne.

Messages in the Corrour books bubble with a sense of innocent delight at this exciting escape from stuffy urban life or cramped domestic spaces. People could adventure and play, flirt and argue, away from the constricting world they knew.

Where else might “two solitary females”, Isabel S McKay and E Marguerite South, who visited Corrour in August 1931, have joked with two Dublin lads. An amusing entry is JDV and WB’s. They lamented the lack of female company on their entrance into the bothy in June 1930 but provided an addendum at 3am, in faint, straggly handwriting that suggests tiredness or drunkenness. The bothy has become a “little paradise” enlivened by two “Glasgow fillies”.

This was a space for fun and reinvention, precisely because you shared it only for a few hours, and you might never see your companions again. That remote intimacy was freeing, exhilarating. And it’s the same today.

Alison and I follow a bend in the path and are greeted with a view of Glen Dee in evening sun, the light falling rapidly behind the plateau, shadows racing across the ground. We make the final journey across the aluminium bridge over the Dee. It’s busy, as Corrour so often was and is. That’s part of the charm, though, that haphazard throwing together of characters for an hour, a night, a morning.

Alison and I won’t be staying inside, it’s too crowded, so we find a pitch for the tent we have brought. We spend a while chatting to fellow travellers against the backdrop of snores from one weary hiker. Tents surround the building, busy with people cooking meals, washing pans, settling down in the warm mid-June air.

Before we leave, we write in the book. If you go back now you can probably read my entry. In bothies, the remote landscapes are intertwined with people and the traces they leave. From the smoke of countless fires that blackens the chimney, to tins of food or dregs of alcohol, everyone leaves imprints. Claerddu bothy in Wales is covered with inscriptions for there’s no bothy book, while Staoineag bothy has a wall of graffiti. Douglas Webster and Douglas Mitchell were particularly grateful in 1929 for the whisky someone had left behind at Corrour, which they used for hot toddies to wash down their “hoosh” (Antarctic survival stew).

We wake up early the next day and set out walking. As we come to the high valley’s endpoint, beneath Lurcher’s Crag, where Aviemore comes into view, we get back into signal range and our phones ping. We had only been taking a break from the ordinary stresses of modern life, but Corrour has provided refuge from darker realities. As the freedom of the 1930s ended, war loomed. Like the women from London, Charles Drinkwater first visited Corrour just before conflict broke out, in June 1939. Little did he know that next time he came, in 1940, the world would be at war, and he would return to active service and to air raids.

Alison and I finally reach Aviemore and feast on crisps and sandwiches, not relishing the prospect of work the next day. We all have to withdraw soon enough from the escapes we find, and time marches on.

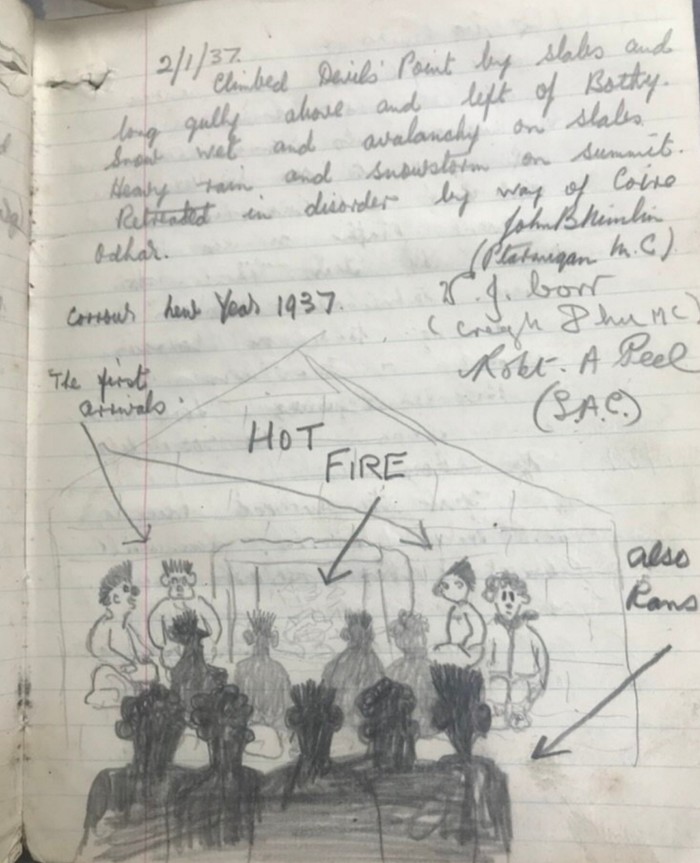

I think of the six members of Creagh Dhu Mountaineering Club who left Aviemore at 1.30am in heavy snowstorms on New Year’s Day 1937 and trekked along the Lairig Ghru. With four bottles of whisky, they endured the blizzard and the mountains in the hope of being “first-footers” to Corrour. First-footing is an old Scottish tradition of being the first person to cross the home’s threshold as the new year begins. Even more fortunate if it’s a young man with dark hair, so legend tells. Make sure you bring a gift, too, perhaps coal to signify warmth for the coming months.

Trudging through the whiteness, they arrived after 6pm but their dreams were dashed as they realised that A Lavery and D McGovern were already there. The pair had taken no chances, making sure to get to Corrour by 12.15am. Lavery’s sketch in the bothy book shows 1937 chasing away Old Father Time.

You can’t escape time in bothies but many visitors find themselves longing to return to the in-between space they provide, seemingly isolated and unchanging. As he left Corrour in 1940, Drinkwater wrote: “Anyway, I’m still hoping to be back here for several days when the war is over.” I leafed through the books, hoping to find his name, but I discovered no other entry. I don’t know if he ever found refuge again in Corrour after the fleeting freedom of 1940.

For more on visiting Scotland’s bothies, see mountainbothies.org.uk

‘Bothy: In Search of a Simple Shelter’ by Kat Hill is published by William Collins on May 9.

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life & Art wherever you listen