From all points of the compass they came, bursts of intense colour flitting across the sepia, drought-ravaged land, like so many dazzling moths.

These were Samburu women, draped in cloth of cerulean and vermilion, metal anklets blinking under the African sun, forearms wrapped in thick, beaded bracelets like coiled snakes, necks and shoulders buried under cascading necklaces of every colour, which the Samburu call mporros, given to women over their lifetimes by their fathers, then suitors, then husbands.

“Neighbouring tribes call us ‘the Butterfly People’,” said my Samburu guide, Kalamon Leogusa, himself cutting quite the dash in his cerise kikoi skirt and his nkerinn cross beads worn like bandoliers. It wasn’t difficult to see why.

The women, many of whom had been walking for two hours, clutched bottles, which they handed to the village matriarch squatting under a giant acacia. She decanted the contents into giant urns and said something to a man in Maa, the Nilotic language the Samburu share with the Maasai of Kenya’s Mara — their more famous cousins. He scribbled notes in a ledger and loaded the urn on to a truck.

This was the daily goat’s milk market — a timeless, ancient scene, you might think. But you’d be wrong. For it was established only two years ago, just the latest example of how the Samburu — semi-nomadic pastoralists who live in the remote, scorched lands of northern Kenya’s Great Rift Valley, between the turquoise waters of Lake Turkana and the muddy whorls of the Ewaso Nyiro river — are adapting to a fast-changing world.

The truck pulled off, and Kalamon and I followed it, slaloming between the acacia and fig trees and the occasional shocking pink of a desert rose. We bounced down into the axle-deep sands of the dry river beds (luggas) that typify the region, and up again, the scenery framed by the jagged, juniper-clad Mathews Range, a 100km-long sky island in this otherwise flat desert landscape.

We passed dik-dik and a huge male greater kudu, with its magnificent corkscrew horns, reticulated giraffes and the odd warthog, ribs bulging against diaphanous skin. An Egyptian vulture stared down from an acacia at the fly-blown carcass of a cow. It was hard to imagine how anything survived in this inhospitable place in normal times. But these, as Kalamon explained, were not normal times, with the Horn of Africa in the fourth year of a devastating drought, which had seen the Samburu lose up to 70 per cent of their cattle — their most prized possession, their wealth fund.

“Do the Samburu believe in climate change?” I asked him.

“We do,” he said.

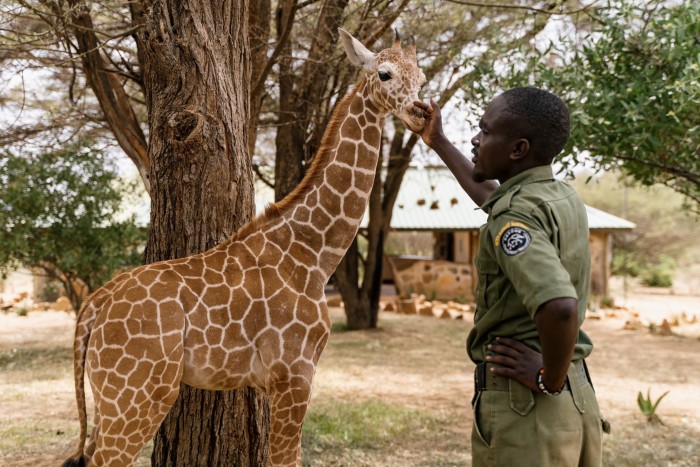

The flatbed had pulled up, the urns were being unloaded. This was the Reteti Elephant Sanctuary, a rescue centre for baby elephants abandoned by their mothers after falling into wells dug by the Samburu. These are getting deeper and more treacherous every year as the water table drops.

Community-owned and run, the sanctuary was opened in 2016, the latest initiative between the Sarara Foundation, which oversees the 850,000-acre Namunyak Conservancy, and the Samburu. The foundation was set up in the late 1990s by third-generation Kenyans Piers and Hilary Bastard, after they visited the area and were horrified by the devastating loss of wildlife through poaching and human-animal resource conflict — local elephant numbers were down to 400 from 15,000; the last of the 4,000 black rhino had been killed for its horns in 1992.

The various foundation projects, including three small-volume upmarket lodges, health centres, schools and the elephant sanctuary, now employ more than 400 Samburu and have brought a vast improvement in living standards and opportunities, not to mention a spectacular recovery in the wild animal population. Giraffe and Grévy’s zebra numbers are recovering; elephant numbers are back up to 4,000.

More wildlife has also meant visitors paying to come and see it. As a result, the Samburu have imposed a moratorium on the killing of wild animals. And where they once fished out abandoned elephants from the wells and left them to die, indifferent to their plight, they now take them to the sanctuary instead.

“Before, a drought like this might have seen Samburu heading for Nairobi, away from their families and culture, or fighting with the Turkana [the Samburu’s despised enemy] over cattle or water,” Kalamon told me. “But now, 60 per cent of the revenue from the lodges goes to the community, and we have opportunities to earn money, which we use to support our villages, buy cattle, go to school and get medical care, so we don’t have to leave.”

The all-Samburu staff at the sanctuary led the orphaned elephants into the enclosure for their feed of the goat’s milk I saw earlier being sold. Each of the 42 elephants being looked after drinks two litres every three hours, 24 hours a day, meaning the sanctuary gets through nearly 700 litres a day. Until 2020, the sanctuary bought powdered milk from Nairobi, at vast expense, until it was discovered that goat’s milk was perfect for baby elephants, so local women started milking their goats like fury and selling it to the sanctuary.

The elephants greedily slurped down the milk. It was heartbreaking to think of these creatures abandoned, alone and distressed, at the bottom of a well, none more so than little Long’uru, whose trunk had been bitten off by a hyena while he was stuck. He is recovering well, and it is hoped that one day he will be released, along with the other orphans, back into the wild.

Kalamon and I walked over a hill and arrived at Reteti House, the latest lodge from Sarara. Opened last year, with all Samburu staff and guides, it is a stunning, sumptuous, four-room exclusive-use lodge run on solar power, with water from a spring, built high like an eyrie into the side of the mountain. It has an infinity pool overlooking a watering hole and a view across the vast Rift Valley plain, dotted with little rocky hummocks, so perfect it seems to come from the Platonic realm.

I ate dinner on the terrace overlooking the savannah. With night falling, the only visible lights in the twilight were the fires of Samburu honey-hunters in the hills, the only sounds the wild cackling of hyenas. The next morning, we drove north, on rutted red-sand roads across the immense thirsting plains of this wild corner of Africa, completely untamed and unfenced, eastern-chanting goshawks darting in front of us, white-crested helmetshrikes chattering noisily in the trees. A jackal eyed our passing from the shade of a bush.

We passed a group of Samburu warriors, or moran, the caste of young men who, for 15 years or so after circumcision until they become junior elders, wander these lands with their grazing cattle, responsible for their safety — from wild animals and from rustling by neighbouring tribes. While out with their cattle, they exist almost exclusively on milk and the blood drawn from the necks of their herd.

They were dazzling in their bright shukas wrapped tightly around their waists; triangles of ochre painted on their cheeks and bare chests; hair, smeared with ochre and animal fat to make it glisten, braided down their backs. On their heads they wore beaded bands, adorned with feathers or the talons of raptors. They clutched long spears and rungus, brightly decorated wooden throwing clubs with a bulbous end.

After two hours, we arrived at Kalepo, an exclusive-use camp of five luxury, secluded tents so remote and hidden in the bush that I didn’t realise we had arrived until Rob and Storm Mason, who run the camp, came out to greet us. Originally from South Africa, the couple arrived in the area a few years back after hearing that the local Samburu community, who had been closely watching developments at Sarara, were looking for investors and were willing to offer a 30-year lease on their land.

The Masons had a torrid time initially. The logistics of building in such a wild place, so far from anywhere, with a limited budget, no metalled roads, and only a short dirt landing strip (guests generally arrive at Kalepo by light aircraft, from Nanyuki, an hour’s flight away) were a nightmare. Then there were the many cultural complications, including the fact that the male warriors won’t eat in the presence of women, thus ruling out a mixed-sex workforce. “We had no idea about the magnitude of the culture here,” said Rob.

Then, a month before the first guest was due, Covid happened. “The community have only done this because they want a return, and suddenly there were no paying guests and thus no $150 a day per guest conservancy fees,” said Storm. “Also, the Samburu thought Covid was a scam. They still do, so there were trust issues. But we’re finally in a good place with them.”

We walked along a dry lugga littered with elephant droppings the size of basketballs. We were accompanied by Emmanuelle Lesampei, one of the 43 local Samburu now employed at Kalepo, eventually arriving at his manyatta, or village. There we met Emmanuelle’s father, the community elder Temba Lesampei, who had just had his 30th child, and we learnt about the gerontocratic, polygamous framework of Samburu culture, how boys become warriors after being circumcised — the most important ceremony in Samburu life — in large batches. How everything was decided on by a council of elders, who convened under a nearby giant fig tree. How wealth was measured by the number of cows owned. How law and order was imposed through a system of curses. How a dead warrior’s body was left out in the bush for the hyenas.

We wandered around the huts, made of wooden poles topped with cow-dung roofs, among the goats and the camels, increasingly being added to Samburu herds because of their resistance to drought. Each of Temba’s five wives had her own hut. Outside one of them was a spear, the sign that this was where Temba would be sleeping that night.

That afternoon in camp, I joined Storm as she held her first-aid clinic, where Samburu women presented themselves and their children for treatment with antibiotics, eyedrops and antimalarial medication. Storm explained how they sent food from the Kalepo kitchen to the local school, so that 60 children had a hot lunch every day. “Guests sometimes come along and help us serve,” she said.

That night, we ate dinner at the camp under a black velvet sky sprinkled with stars. A huge Verreaux’s eagle owl, with bright pink eyelids, fed by the Masons after they found it as an orphaned chick, swooped down on the sand for scraps. There was a rustle in the scrub, then a herd of elephants emerged at the watering hole, dug by Rob — along with four wells for the local community — right in front of us.

The next day, we walked out again, through the scrub, to the “singing wells”, holes up to 20ft deep, dug by the Samburu into the dry riverbed, from where the men worked as a chain gang handing up buckets of water to fill a wooden trough for their animals. While they worked, they sang a guttural rhythmic chant, praising their precious cattle, luring them to drink.

Afterwards, under the toothy crag of the sacred Kimaning mountain, we watched as the warriors arrived for the daily practice of their skills, sporting punkish feather mohawks, beaded necklaces dripping with silver dollars and knee-length striped football socks — evidence of young Samburus’ new obsession with the English Premier League, a recent arrival via the internet. They formed a tight group, ululating, taking turns to pogo high into the air, flexing only at the ankle, and then competed against each other, throwing spears through moving hoops with incredible precision and firing arrows into elephant-dung targets, all filmed on mobile phones, to be uploaded later to TikTok.

I asked Kimeron Loltienya, who worked at Kalepo, what he thought about the future of the Samburu. In perfect English, he talked about the Maasai: how many of them had sold their land and their cows, only wearing traditional dress when they danced for tourists for money. “We feel pity for them, our brothers,” he said. “But we won’t make the same mistakes. Our culture is too strong. Through education, we are learning about climate change, how our community, livestock and wild animals can live together, along with tourism. I have already bought two cows from working at the lodge.”

As we walked back to Kalepo, Kimaning blushing scarlet and then fading to grey, I asked Rob about the future. He talked about his desire to reintroduce the black rhino — “which would secure enough tourism revenue for the community to become self-governing and resilient” — and plans to help the Samburu plant agave, a drought-resistant succulent, which would restabilise the overgrazed land and, through cultivation for agave syrup, provide a sustainable income and autonomy for the Samburu in the uncertain years to come. “Some conservation models in the past gave communities just enough money to get by, keeping them dependent on the donor,” he said. “Be nice to break that mould.”

Wilfred Thesiger, the 20th-century explorer, spent 15 of his later years living with the Samburu, whose gentleness, bravery, honesty and friendship he greatly admired. “I craved for the past, resented the present and dreaded the future,” he once wrote.

For these traditionalists in a world of change, that future would still seem to be very much up for grabs.

Details

Mike Carter was a guest of Journeys by Design (journeysbydesign.com), which offers tailor-made cultural and wilderness journeys to northern Kenya and elsewhere in Africa. A private five-night trip, with three nights at Kalepo Camp and two at Reteti House, which has a direct link to the elephant sanctuary, costs from $8,990 per person, including exclusive use of both Kalepo Camp and Reteti House, full-board, and all internal private charter flights

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter