The boardroom bust-up at Baillie Gifford’s flagship Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust has put the oversight of these venerable structures under an awkward spotlight.

Last week the 114-year-old investment trust asked one of its non-executive directors to leave following a searing critique of the firm’s corporate governance. This week the trust announced its chair, Fiona McBain, would step down at the annual general meeting in June.

The concerns of Amar Bhidé, the recently departed director of Scottish Mortgage, appeared to stem from the company’s expansion into unquoted holdings. He said the board did not have the requisite experience and was led by a chair who had ceased to be independent, as she had served as a director for too long.

He added that the managers were not sufficiently resourced to monitor the trust’s diversification out of quoted stocks into unlisted securities. Baillie Gifford rejected these allegations and said it had a team of 37 monitoring private companies.

Scottish Mortgage also said the trust looks to own late-stage private companies that are not looking for operational support — a quarter of the trust’s private companies are valued at over $2bn.

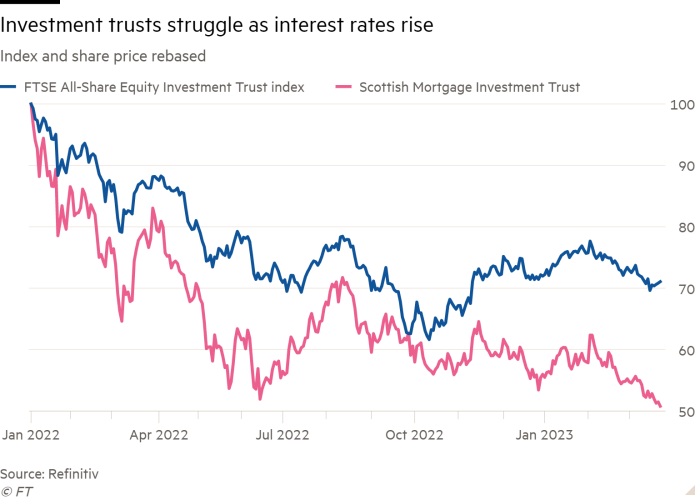

The saga at Baillie Gifford comes as rising interest rates have knocked the share price performance of several investment trusts.

With their closed-ended structure, trusts have offered a way for retail investors to own privately held companies, because investors could trade a trust’s stock without disturbing the underlying portfolio.

Such companies can have more investment potential than bigger groups but are often riskier and provide less information. Questions are now being raised about how such holdings have been managed.

Private holdings

Scottish Mortgage has owned private companies since 2012, with a 30 per cent maximum for the share of the portfolio in private companies at the point of investment.

But as public markets have fallen at greater speed than valuations in private markets, the proportion of the fund in private holdings has grown. At the end of February, unquoted holdings made up 29.9 per cent of the Scottish Mortgage portfolio.

James Carthew, head of investment trusts at research company QuotedData, says this puts the managers in a tight spot: if the cap is not lifted the trust risks being unable to invest further in portfolio companies, so its holdings will get diluted.

Other analysts have questioned if the valuations investment trusts ascribe to private holdings reflect accurate prices, given the real value only emerges in a sale. Broker Winterflood’s private equity “growth capital” sector, which includes five investment trusts mainly owning unquoted companies, is currently trading on an average discount to asset value of up to 50 per cent.

Scottish Mortgage is now trading at discount of 18 per cent, compared with an average discount of 9 per cent for its peers in Winterflood’s global investment trust sector. Bhidé criticised the board for not doing enough to narrow the discount, by buying back trust shares. Scottish Mortgage said it had bought back 2 per cent of shares issue last year.

Carthew said buying back shares was difficult because the trust’s gearing — the loans which can amplify returns — was already high at 15 per cent, according to Winterflood data, which shows a sector average of 6 per cent.

Fees

Another popular investment trust under scrutiny is RIT Capital Partners, the trust that runs money for the Rothschild family, which now has 11 per cent of the portfolio in unquoted companies and a further 28 per cent in private equity funds.

Analysts at Investec estimate that upcoming writedowns in these holdings could prompt a 4 per cent fall in the trust’s overall asset value.

But Investec analyst Alan Brierley’s main concern regards its fees, as £55mn of share-based payments have been paid to the managers over the past three years, a period when the trust’s share price has materially underperformed its target growth rate.

Brierley said the trust was “simply uninvestable on cost grounds alone.” Despite the trusts’ fact sheet showing an “ongoing charges figure” of 0.89 per cent, its latest key information document (KID) shows an all-in annual cost of 5.44 per cent. The equivalent KID figure for Scottish Mortgage is just 0.64 per cent.

RIT said annual incentives to employees are capped at 0.75 per cent of NAV and have never come close to this level. It added that over the past 10 years, the net asset value had grown at around 10 per cent annually.

Meanwhile, shareholders questioned the payout to managers at Chrysalis in 2021. The trust paid £117mn in performance and management fees at the end of its third year trading, based on estimated valuations of its private holdings, notably Swedish fintech Klarna. Soon afterwards, the investments’ value plummeted as markets fell in 2022. Chrysalis’s share price is down 70 per cent over the past 12 months.

Brierley said that while there has been “consistent improvement” in governance in recent years, “pockets of complacency remain, with some companies appearing to live in a bygone age”.