Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Iron ore bulls are thin on the ground these days — as are those willing to dig into large iron ore miners such as Rio Tinto. Yet the future, for the Anglo-Australian group, is not nearly as anaemic as it may seem.

Rio is not alone in generating little excitement. Mining as a whole is going through the glum end of the commodity cycle. Chief executive Jakob Stausholm has managed to steady the group after it dynamited rock shelters sacred to Aboriginal tribes in 2020. But, as Rio prepares for Stausholm’s succession over the next two to three years — not least by promoting potential candidate Bold Baatar — remaining headwinds are all too apparent.

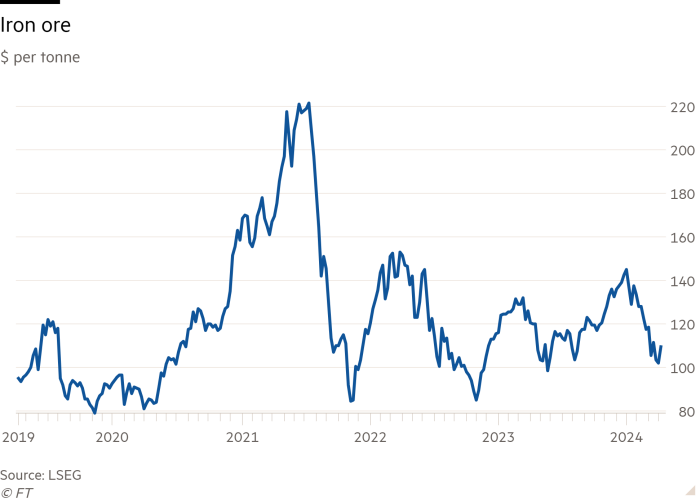

The main one is Rio’s reliance on iron ore, which in 2023 accounted for more than 80 per cent of group underlying ebitda. The metal is currently having a horrible time, down almost a quarter since the start of the year to $104 per tonne. China’s overbuilt and faltering property sector does not help sentiment. Longer term, too, demand is forecast to be roughly flat as increased steel requirements will largely be met by the increased availability of scrap.

Even accounting for natural depletion rates of existing mines, this is not a market that can withstand large supply additions. Yet that is precisely what it is facing. The Simandou project — partly owned by Rio — is forecast to come on stream this year and add, at peak, perhaps 15 per cent to the seaborne iron ore market, according to Ben Davis at Liberum. That will cause iron ore prices to fall.

That helps explain why Rio screens so cheaply, even in the context of the depressed mining sector. It trades at 4.5 times forward ebitda, on Goldman Sachs’s estimates, compared with a sector average of 5.5 times.

Yet investors may be underestimating the rate at which Rio is evolving. Its capital employed by segment arguably provides a better guide to the group’s future commodity footprint. On this basis, its $21bn of copper assets are larger than its iron ore business. That reflects Rio’s $15bn investment into the giant Oyu Tolgoi copper mine in Mongolia, where production is just starting to ramp up.

While it is hard to get excited about iron ore, copper does have a bit more of a shine to it. A key feature of all things energy transition, demand is expected to roughly double by 2040. And supply shocks are expected along the way, with the price of forward contracts for delivery later this year at a record premium to today’s spot. Rio’s increasing exposure might add some colour to its equity story.