Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Pakistan’s traditional political power-brokers have unveiled a new coalition government, breaking a two-week impasse following elections, but the incoming administration will be quickly tested by the country’s dire economic circumstances.

The Pakistan Muslim League-N of three-time former prime minister Nawaz Sharif and the Pakistan People’s party, led by Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, announced late on Tuesday they had agreed to form a government.

The parties, which have historically dominated Pakistan’s politics, came second and third in the February 8 elections, when independent candidates loyal to imprisoned former prime minister Imran Khan shocked observers by winning the most seats despite suffering a military crackdown.

The new government will be led by Shehbaz Sharif, Nawaz’s brother, while Zardari’s father Asif Ali Zardari, the husband of slain former prime minister Benazir Bhutto, has been put forward for the mostly ceremonial role of president.

The administration will be forced immediately to contend with Pakistan’s acute economic plight, after Islamabad narrowly averted default last year with the help of an emergency IMF lending agreement. That programme is due to expire in April, meaning the country’s new rulers are expected to need to return to the fund for more support.

The populist Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party, meanwhile, has claimed that its candidates were robbed of a majority by vote rigging and vowed to topple any rival coalition, raising the prospect of more political instability that could derail any economic recovery.

Fitch Ratings warned this week that finalising a new IMF deal was “likely to be challenging”, but Pakistan had little choice: “Failure to secure it would increase external liquidity stress and raise the probability of default,” the credit rating agency said.

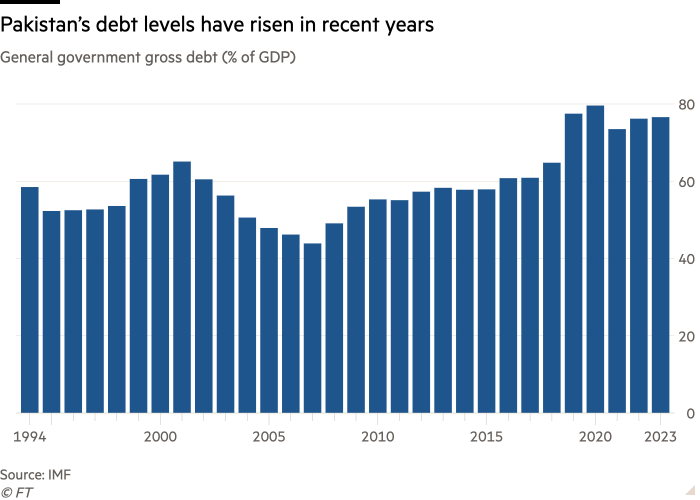

Pakistan’s debt has soared since 2007 as authorities failed to invest borrowing from international bondholders and countries, including China, into productive sectors. “Debt accumulation has been overwhelmingly used to continue fostering a consumption-focused, import-addicted economy,” according to Tabadlab, a think-tank in Islamabad.

This means the government has had to borrow even more in order to meet its existing debts.

As a result, most government revenues now go to repaying interest, while Pakistan’s foreign reserves, at $8bn, are only enough for around six weeks’ worth of imports.

Tabadlab warned on Sunday that this vicious cycle had become “unsustainable”.

“Unless there are sweeping reforms and dramatic changes to the status quo, Pakistan will continue to sink deeper, headed towards an inevitable default,” it said.

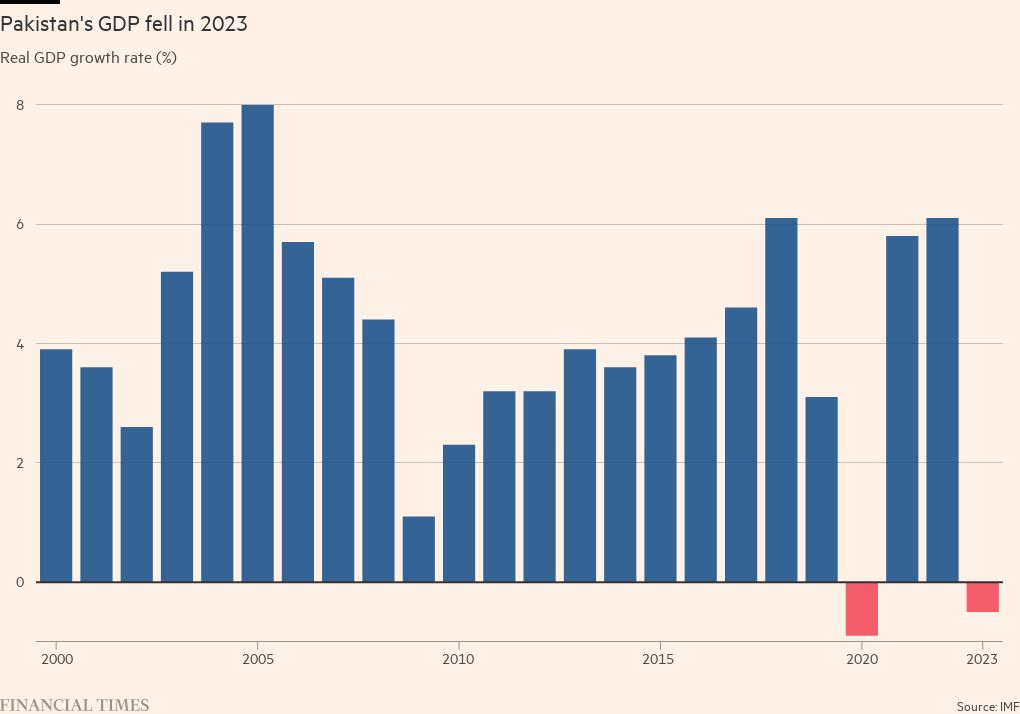

One reason for this is weak growth. Unlike in nearby India or Bangladesh, Pakistan has been unable to sustain growth levels and suffered regular boom-and-bust cycles, with the economy contracting in 2023.

Asad Sayeed, an economist at the Collective for Social Science Research in Karachi, said this was unlikely to change until Pakistan increased exports and boosted tax collection enough to fund badly needed government investment. “Unless you resolve [this], you’re not going to grow,” he said.

The most painful manifestation of Pakistan’s economic crisis has been inflation, which peaked at 38 per cent last year and remains near 30 per cent.

Pakistan’s import-dependent economy was hit by the surge in commodity prices following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Subsequent cuts to fuel subsidies — a condition of the IMF lending — exacerbated the pain.

Sayeed said he thought the worst was over, unless the new government succumbed to pressure to increase spending, such as offering additional subsidies. “If the new government starts behaving badly again . . . then [inflation] will increase further.”

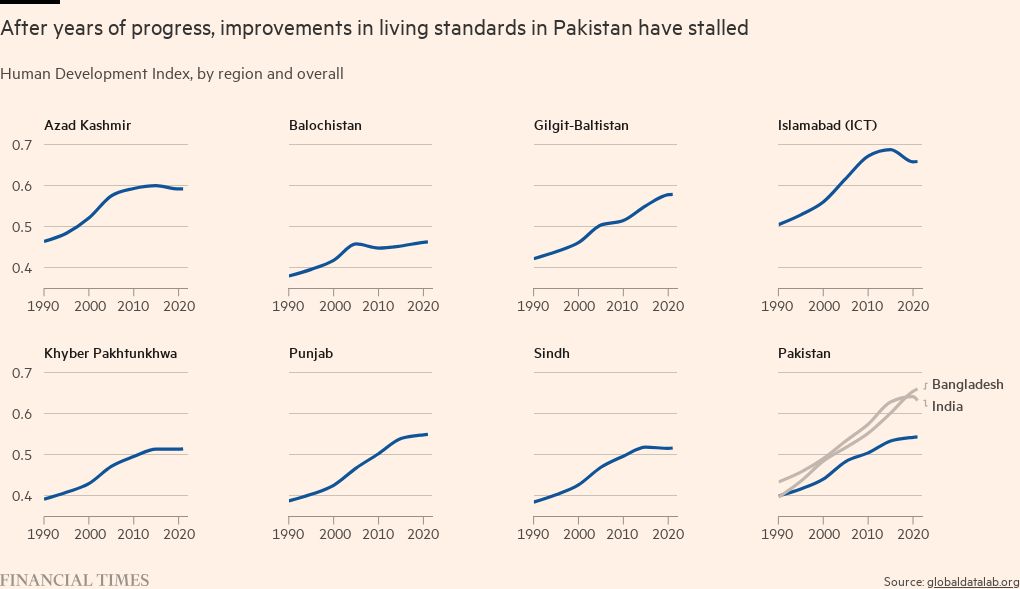

One consequence of Pakistan’s tepid growth is that it is not able to create enough jobs. More than half of the country’s population is under the age of 30, and the majority of working-age women do not participate in the country’s labour force due to lack of opportunities and entrenched patriarchy. Improvements in living standards have also stalled, with poverty increasing.

The economic malaise has fuelled popular anger towards the government, which Shehbaz Sharif headed in 2022 and 2023 after Khan was ousted by parliament. It also increased the appeal of the PTI.

Analysts said Pakistan needed both a new IMF programme and painful economic reforms to avoid a debt restructuring. But while a new government will offer some certainty, it may struggle to improve Pakistan’s parlous finances.

“The good thing [would be] that there’s a government,” said Bilal Gilani, a political scientist. “The bad thing is that the government might be much weaker.”