“I am very grateful to be living my dream,” she says. “When I first started doing art, I wasn’t thinking about becoming a famous artist, all fancy. I just had the very simple mindset of wanting to fulfil my dream and go and learn.”

Nearly five decades since she made that one-way trip from Hong Kong to Australia, Leung is reflecting on a journey that proves that perseverance can make any dream come true, she says, no matter how long it takes for you to realise what you really want.

“I wasn’t happy at all with my circumstances in Hong Kong,” Leung recalls during a recent video interview. “I couldn’t see much of a future there.”

7 most popular arts stories in 2023, from nude canvases to ‘gross’ sculptures

7 most popular arts stories in 2023, from nude canvases to ‘gross’ sculptures

Named Cheng Wing-yi by her parents, young Pamela was raised in an underprivileged and traditional Chinese family, she says. She started working full-time after finishing secondary school, first as a bank teller.

“The job was considered ideal for girls back then, like being a teacher or a nurse.”

However, Leung – who adopted her husband’s surname in the 1970s – has always wanted to do something creative. She studied an evening course in graphic design for a year, and eventually quit her safe job at the bank to work at a window-dressing company – more fun, but with very little pay, she says.

Her boyfriend at the time knew somebody who lived in Sydney, and brought to her attention that the government had been granting general amnesties for illegal immigrants since 1974. Leung decided to take a risk.

“I was 25 and looking for a new life. I got a three-month holiday visa and left Hong Kong in 1976, with no family, no friends, no language, no skill – just a fantasy dream and the belief that I could survive as long as I had my two hands.

“I remember very clearly that as I walked to the gate at the airport, I said to myself: ‘I’m not going to go back.’”

The first few years were particularly tough. Speaking little English, Leung worked almost every day as a waitress at a Chinese restaurant and as an assistant at a creative studio.

A year later, Leung’s boyfriend joined her in Australia, where the pair got married and became legal residents. By the 1980s, the pair had two children.

In 1987, she started a childrenswear business, which she ran for 10 years. Leung says she is proud of how she became financially secure during that time and gave her two sons more advantages than she had growing up. But when profits started to dwindle, she decided to ride on the wave of Australia’s booming artisanal coffee culture and opened a cafe in 1998.

I am interested in relationships, connections, social justice and the repetitions and contradictions of everyday life

In 2009, her priorities changed dramatically. In the first year of her unofficial retirement, Leung separated from her husband. He wanted the conventional: a job, a roof over his head, a wife and children. She realised she wanted more.

That same year, Leung enrolled as an undergraduate at the National Art School in Sydney.

“In the back of my mind, I was always thinking that when I retired, I would learn how to paint. I was 59 when I started my undergraduate degree. I spent seven-and-a-half years in art school and got three degrees, including my master’s in 2016. I’m very, very happy.

“For the first 30 years that I was in Australia, it was just work, work, work. I would say the first three years in school were the best time of my entire life. I felt like a little child with so much to learn.”

Sporting short, grey hair in a stylish quiff, the bespectacled and youthful 72-year-old says her practice is informed by the everyday life and perspective of an immigrant.

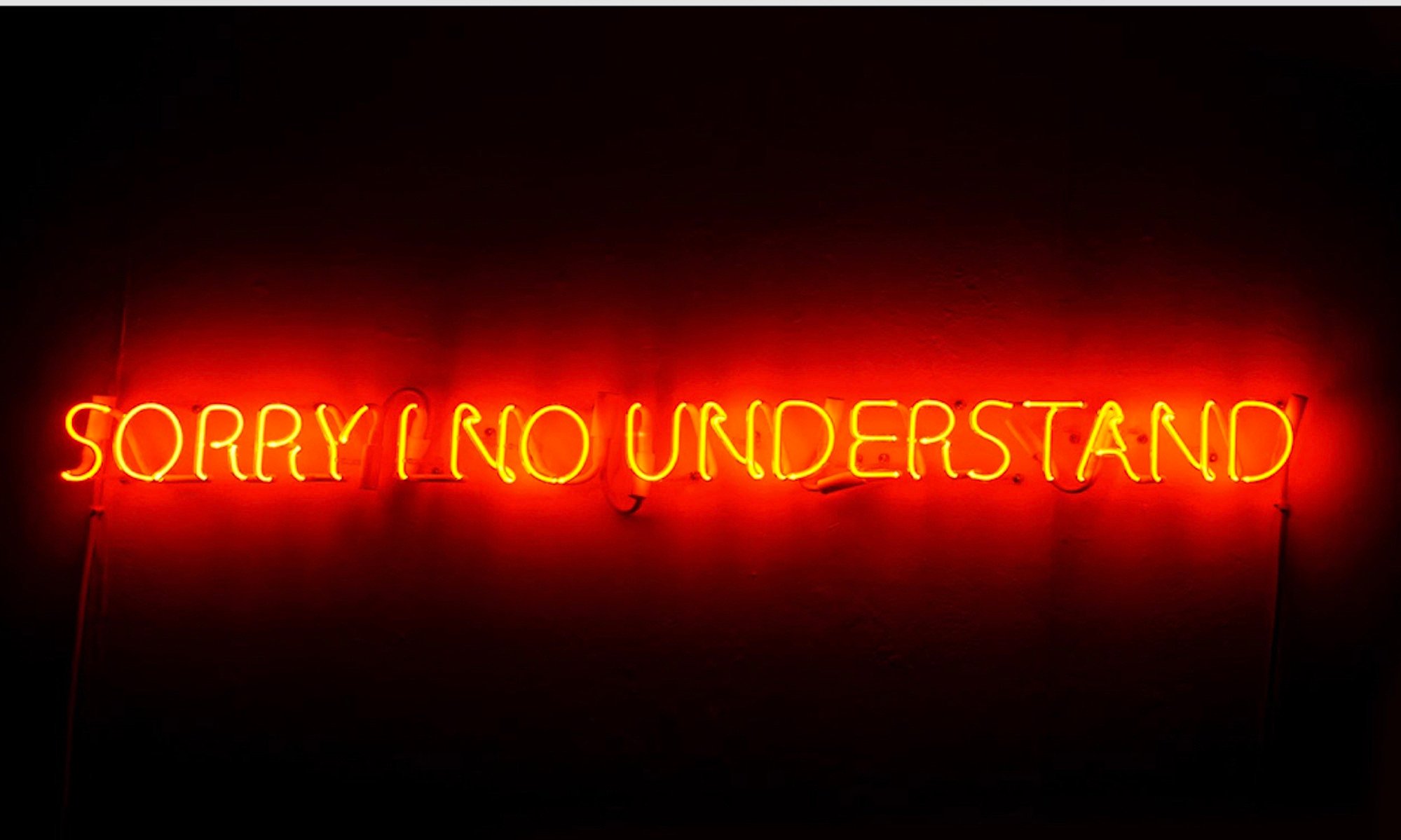

In 2018, she made a neon light installation called Sorry I No Understand, which she showed with broken egg shells on the floor beneath it to suggest a sense of cultural vulnerability commonly experienced by migrants.

Vermilion has become her signature colour. Red – the colour of her glasses – is a lucky colour for the Chinese, but that’s not the reason why she chose it.

“When I talk about immigrants, I am talking about people and the real colour under our skin. No matter what your skin colour is, you are just red underneath.”

Red is also political. In 2022, she made an installation and film called Where is the Red Line that was shown as part of a local Lunar New Year exhibition – the title a reference to censorship and surveillance, as well as her own inseparable connection to the city of her birth.

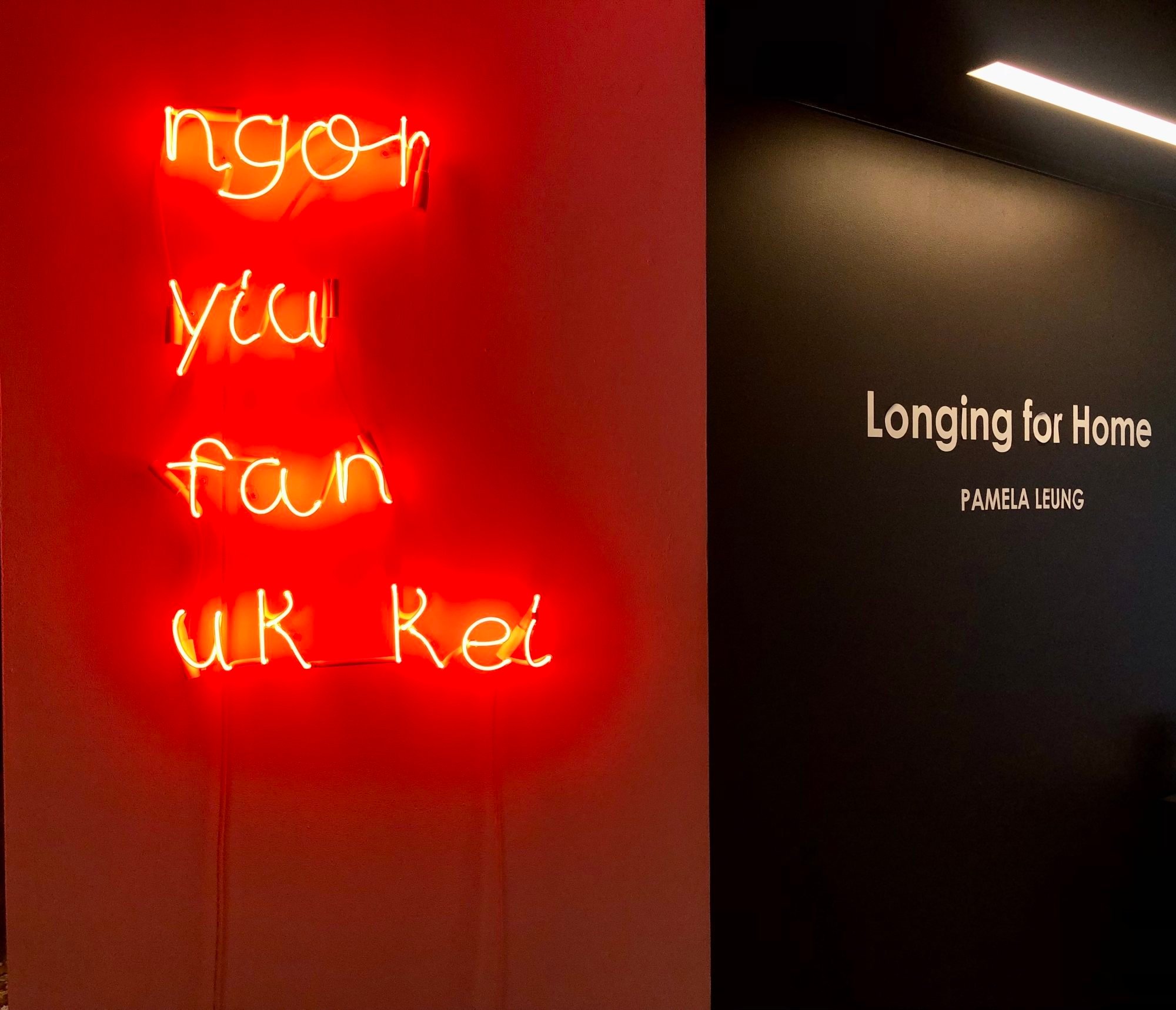

That work was later taken to Sheffield, in the UK, where she joined a number of Hong Kong-born artists now living in Britain in a show about the experiences of displacement and cultural longing.

Leung often expresses her affection for Hong Kong through her art, perhaps more so since witnessing the 2019 anti-government protests in the city and subsequent political changes from afar.

In 2020, she made a large, rectangular work called Safety Blanket from old business documents she recycled by hand. The slow process involved tearing up each individual document, and later painstakingly stitching the recycled pieces of paper together. Each section was then marked with the international symbol for luck: a four-leaf clover.

In May 2022, Leung returned to Hong Kong to perform Bearing wound, honouring suture alongside writer and independent curator Yang Yeung, at Tsuen Wan’s Centre for Heritage, Arts and Textile.

Exploring themes such as pain, solitude, nostalgia, longing and homecoming, the collaborative performance piece was centred on a chair, which served as a physical reminder of absence and symbolised both loss and the hope for reunion.

Because of the political nature of her art, Leung has since decided not to visit Hong Kong again for the foreseeable future, citing her worries about growing censorship and surveillance in the name of national security in the city.

“Under the circumstances [I won’t] be feeling safe at all, even though I just make art to express myself,” she says.

Leung continues to show her art regularly. Having participated in several group shows in 2023, she is preparing for “Assembly”, an exhibition of work by eight Hong Kong-born artists at the Australian National University that opens on February 12.

“I am interested in relationships, connections, social justice and the repetitions and contradictions of everyday life,” she says.

“I apply my own experience to my art, but at the same time, I am not talking about myself.”

“Assembly”, CIW Gallery, Australian Centre on China in the World, Australian National University, Canberra, Feb 12-May 24, 2024.