More than $400bn in market value has been wiped from European tech companies since the peak of the 2021 boom, as venture capital dealmaking hit a wall at the end of the summer.

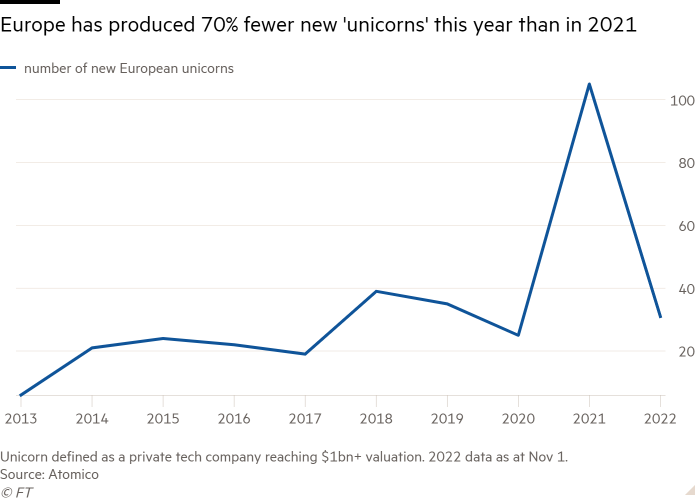

The continent’s start-ups were beneficiaries of a funding frenzy in 2021, leading to the creation of more than 100 “unicorns” — tech start-ups valued at more than $1bn.

That figure has fallen to 31 so far this year, according to a report by London-based venture capital firm Atomico, the lowest level since 2017, excluding the coronavirus pandemic year of 2020. More than 14,000 European tech workers have been laid off, Atomico estimates.

The trend is a reflection of investor wariness of high inflation, rising interest rates and the war in Ukraine. The funding crunch represents the first true test of the European tech scene since a new generation of homegrown companies, led by the likes of Spotify, Revolut and King, became international successes.

“Our view is the challenging macro will persist” well into 2023, said Tom Wehmeier, partner and head of research at Atomico. “There’s no going back, at least for a very long time, to the conditions we saw at the end of 2021.”

Since it began in 2015, Atomico’s annual “State of European Tech” report has charted — and cheered — the rise and rise of start-ups in London, Paris, Berlin and Stockholm, as the region appeared to be finally bridging a decades-long funding gap with Silicon Valley.

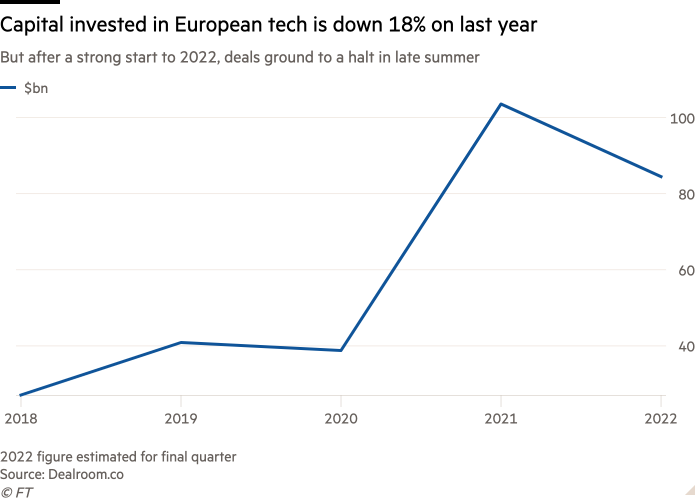

The $85bn invested in European tech this year will still be more than double the totals of 2019 or 2020, Atomico estimates, though the second half of 2022 saw a sharp pullback with only 37 funding rounds worth more than $100mn, compared with 133 in the first half.

Separate research published last month by another venture firm, Accel, based on analysis by Dealroom, found that more than 200 VC-backed unicorns in Europe have spawned more than 1,000 new start-ups, thanks to what they call “founder factories” such as Delivery Hero, Criteo and Klarna.

Even VC veterans are struggling to make sense of the moment in start-up financing, amid macroeconomic and geopolitical jolts.

“I’ve been in this game for 20 years and it is exceptionally hard to read the tea leaves at the moment,” said Nic Brisbourne, managing partner at London-based Forward Partners, which has a £95mn portfolio of early-stage tech companies. “I feel a real lack of confidence that if I put money in now, will that company be able to raise money again in the next 12-18 months?”

Investors say that confidence, not capital, is the problem. Atomico estimates there is still around $80bn worth of “dry powder” available in Europe: venture capital funding that was raised in the boom years and has still not been deployed by investors.

Cautious investors could eke that out for years. At a recent London event hosted by Accel for fintech start-ups and investors, Eric Boyle, partner at tech advisers Qatalyst Partners, said he expected the drop-off in deal activity to last for a while, especially with the public markets effectively closed to new listings. After 86 initial public offerings at a $1bn-plus valuation in the US and Europe last year, there have been just three this year.

“We’ve already had a few people ask us when the IPO window reopens,” Boyle said. “We don’t even think about it. The answer is not soon.”

Unless they need capital urgently, most start-ups are avoiding financing activities, especially after so many raised last year. For a fintech start-up, raising now might mean accepting a valuation multiple of up to 10 times their next 12 months’ revenues, while investors were paying 40-50 times last year, Boyle suggested.

This year’s slowdown also reflects that the frenetic pace of dealmaking last year pulled forward many investments that would typically have happened over the course of a few years.

“Normally we fund a great entrepreneur with a great idea,” said Harry Nelis, partner at Accel in London. “Several months ago, a lot of great entrepreneurs were financed who still didn’t have a great idea.”

The expansion of US tech investors such as Sequoia, Lightspeed and General Catalyst into Europe over the past couple of years only accentuated that “fear of missing out” among local VCs, even as they hailed it as a validation of the region’s tech maturity.

Some American firms are pulling back again, particularly so-called “crossover” funds such as Tiger Global and Insight Partners, fearing that a recession may last longer in Europe than in the US. The number of US investors involved in deals of more than $100mn in Europe has fallen 22 per cent so far this year to 122, after jumping from 48 in 2020 to 157 in 2021.

Despite the turmoil, some start-up deals are still getting done, mainly in more sedate corners of business software instead of racy crypto or ecommerce bets.

Paris-based Pigment, which makes business planning software, raised $65mn in September. “It’s good market conditions for us,” said Eléonore Crespo, Pigment’s co-founder. “Our goal is to help companies navigate uncertainty.”

However, after a period of strong growth, Europe’s tech entrepreneurs are facing more sceptical investors and straightened times.

“The last two years were really an aberration,” said Jan Hammer, partner at Index Ventures, one of Europe’s largest venture firms, which raised a new $300mn seed fund last month. “The market got carried away.”

Additional reporting by Ian Johnston