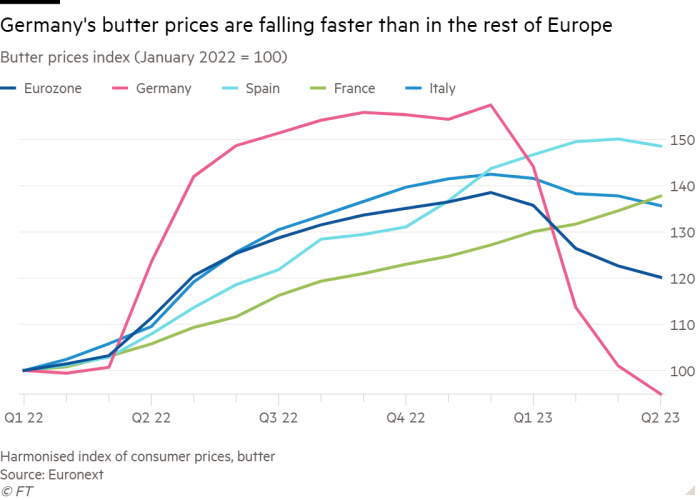

Something unusual has happened to the price of butter in Germany this year — it has fallen sharply even as the cost of many other foods kept rising at double-digit rates.

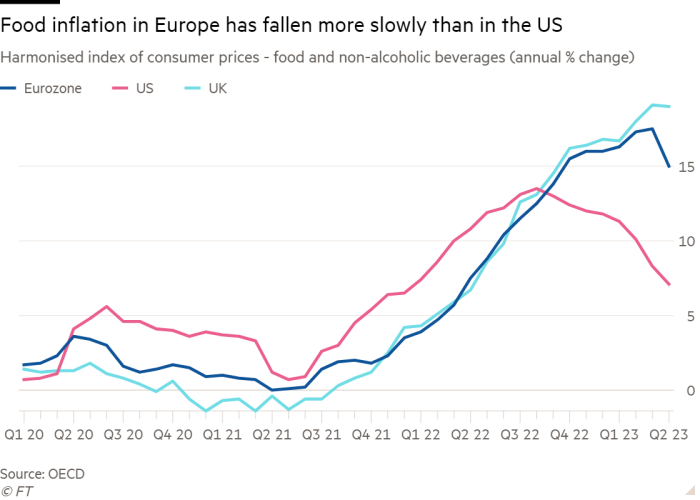

Following a dip in energy prices, surging food costs have become the main source of inflation for the eurozone consumers. They are up 20 per cent since the start of last year, causing alarm among politicians and central bankers.

But economists and industry executives increasingly believe the factors behind a fall in the price of German butter — down almost 30 per cent since December as dairy producers’ costs have fallen — will soon begin to have a broader impact.

If other food prices follow suit, it would not only boost strained household budgets, but also help eurozone inflation to keep falling fast enough for the European Central Bank to stop raising interest rates this summer.

The German butter market is somewhat unusual.

Often prices are negotiated between maker and retailer every few weeks, allowing lower producer costs to be reflected much quicker than in other markets, where contracts are renewed only every six months, or even every year in the case of branded products.

Butter prices in the rest of the eurozone have not fallen as fast and in April they were still rising in some countries, such as France and Spain.

However, Thomas Carstensen, senior vice-president of global trading at Denmark’s Arla Foods, which makes Lurpak and Anchor butter as well as cheeses and milk, said the German market could be “an early indicator” for the price of other dairy and food products.

Its fall reflected a drop in dairy producer prices that stemmed from lower cattle feed and energy costs, as well as lower consumption that led to a glut of milk production late last year.

Other producers of dairy products agreed. “Cheese prices have already fallen in Germany and when the July contract for milk is agreed, I can see a price cut there,” said Eckhard Heuser, general manager of the German dairy industry association. He predicted that German milk prices could fall from €1.15 per litre back below the psychologically important “magic price” of €1 per litre, adding: “There is pressure in the market”.

For now, surging prices for others foods are having a marked impact on demand.

The value of retail food sales in the eurozone has risen almost 10 per cent in the past year but they are down almost 5 per cent in volume terms, after adjusting for inflation.

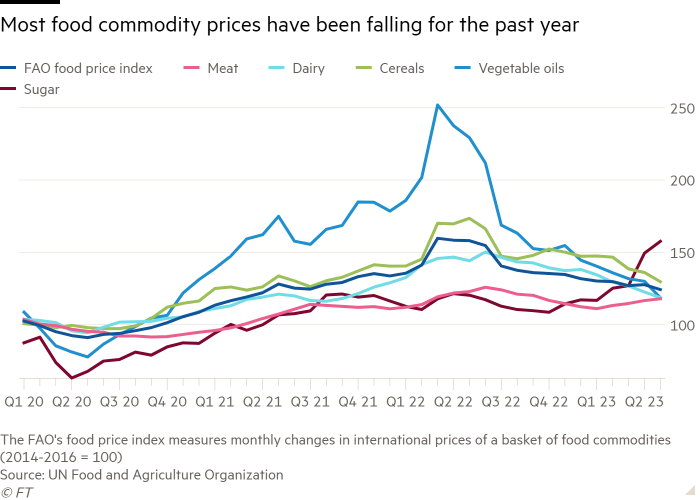

Lower demand is eventually expected to put more downward pressure on wholesale prices, which have been falling globally since last summer. Those lower wholesale prices, coupled with falling energy and commodity costs, should be passed on to shoppers — at least partially. “It is not one-to-one, but it should start to feed through steadily,” said Carstensen.

Most economists are confident the surge in food inflation has peaked, after it fell for the last two months, from a high of 17.9 per cent in March to about 14 per cent in May. But there is still great uncertainty over how fast the price surge will dissipate in the months ahead.

“If you look at the mechanics of the market, the sharp falls we have seen in energy prices and food commodity prices should feed through to the end prices paid by consumers with the usual lag of about three to six months,” said Ludovic Subran, chief economist at German insurer Allianz who used to work for the UN’s World Food Programme.

Allianz forecast eurozone food prices will decline so much that food inflation will turn negative by early next year. But Subran warned that some 10-20 per cent of recent food inflation was not explained by higher costs, suggesting price-gouging by companies. That greedflation could put a brake on price falls.

“There is some oligopolistic behaviour, especially among the producers, distributors and transportation companies,” he said.

There are other potential reasons why food inflation could be sticky. They include higher wages, rising borrowing costs and the slow pass-through of earlier energy and commodity price surges.

“Food importers and producers typically lock-in long term wholesale contracts, so changes in commodity prices feed through to their cost base with a lag,” said Gerardo Martinez Garcia, an economist at French bank BNP Paribas. “So we expect them to benefit from cheapening commodities only slowly.”

BNP Paribas expects eurozone food inflation to end this year at 8 per cent and remain above 4 per cent in the first half of next year.

Others said food inflation was on a clear downward path, but they were doubtful it would fall as fast as it rose. Ariane Curtis, an economist at Capital Economics, said the acceleration of eurozone wage growth above 5 per cent in recent months could slow the decline.

“Strong wage growth is one of the factors keeping food inflation so elevated,” she said. “The historical relationship between food inflation and agricultural prices has seemingly broken down recently and so it’s unlikely that the fall in energy input prices in itself will be enough to drive food inflation negative by the end of the year.”

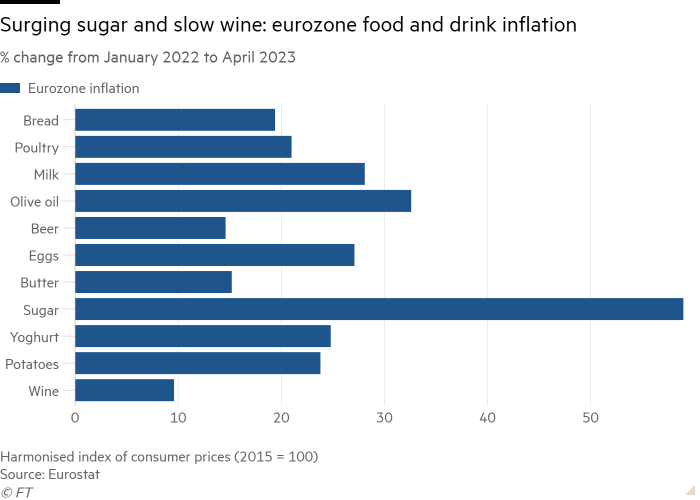

Many national specialities in Europe have jumped in cost by unprecedented amounts since the start of last year — just before food and energy commodity prices were sent soaring by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Spanish omelettes have been hit by a one-third jump in egg prices and an almost 40 per cent rise in the cost of oil to fry them. Belgium’s chip lovers have had to deal with a 27 per cent rise in potato prices. Croatian oenophiles are paying a fifth more for local wines, while the sugar used to make Italian panettone now costs two-thirds more.

Higher food prices hit the poorest people hardest because they spend a higher proportion of their income on groceries — partly explaining why food banks have experienced a surge in demand across Europe.

Economists said food inflation was particularly important for the ECB because it had extra sway over consumers’ perception of inflation.

“Not all inflation is equal,” said Katherine Neiss, chief European economist at US investor PGIM Fixed Income. “These high-frequency purchases — like food — are noticed more by people when their prices change so this feeds into things like their wage demands.”