When he was growing up on council estates in east London in the 1980s, video games offered Larry Achiampong the kind of solace and safety the outside world didn’t. The genre-bending artist started gaming aged four, playing 8-bit games such as Duck Hunt and hack-and-slash Shinobi. “My mum was working so many jobs, and where we lived you had kids getting up to all sorts, there were no activities, there weren’t children’s centres, there was nothing like that then,” says Achiampong. “Her knowing we were indoors playing video games was better than us being on the street.”

Achiampong, 39 and now a father himself, is still an avid gamer — when I call, he hits pause on a game he is playing with his children, popular Japanese release NieR:Automata. Set in a dystopian future with a complex storyline centred around cyborgs and androids who attempt to replicate human emotions, it’s not dissimilar to the kind of clashes between technology and humankind that appear in Achiampong’s artworks. His sculptures, installations, performances and films evince the opprobrium of racism and classism through epic storylines, often accompanied by emotive narration and musical scores composed by Achiampong himself.

For the past decade, Achiampong’s works have been preoccupied with video games. Take the Relic Traveller project, a body of work he began in 2017, which features in his touring solo exhibition Wayfinder, now at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead. The multidisciplinary work centres around a fictional pan-African alliance of travellers: in a series of films, they traverse the deserted, post-apocalyptic terrains of a near-future in search of testimonies and artefacts that speak of the devastation wreaked by capitalism and colonialism. Achiampong’s interest in world-building extends into life-size avatar-like recreations of the explorers; their pan-African flag, appliquéd with 54 stars for each of the African nations, also unfurls in the galleries, its symbols referring to Africa’s past and possible future. (Achiampong himself has Ghanaian heritage.)

The treatment of motion and time in Achiampong’s speculative works also draws on gaming influences. The sweeping, eerily empty vistas in “Wayfinder” (2022), Achiampong’s Bafta-nominated film, recall the settings of 3D games of the 1990s and 2000s. “Wayfinder” is set during a pandemic, and follows a cloaked protagonist on a six-chapter journey across England, from Hadrian’s Wall to Margate, gathering testimonies and histories of displacement that are recounted in vox pops and voice-overs. The film is in part a love letter to benchmark-setting games such as the immersive 3D Metroid Prime (2002) and Tales of Symphonia (2003), an action role-playing game set in part in a world declining for lack of an essential life force. “Wayfinder” is Achiampong’s answer to British Romanticism — but in the place of the Byronic male hero, the central character is a young black woman who considers her relationship to the land, and who can control or claim ownership over it.

Aspects of agency, the ability to control one’s environment and find community through games, are among the reasons Achiampong wants to counter the moralising consternation surrounding gaming that began in the 1980s, arguing that it would inculcate violence and putrefy children’s brains — an attitude that is still common today. As an undergraduate at the University of Westminster and MA student at the Slade, “I was told gaming was juvenile and didn’t mean anything.” But gaming for many is far more open and accessible than museums. “People who experience neglect, violence, people of colour, trans folk, queer people . . . we have been able to fortify ourselves within these spaces we can nurture and build for ourselves,” says Achiampong. “Gaming is still teaching me a lot, in terms of practical knowledge but also emotionally. Games are just like a piece of literature, and they can sit with you, and become timeless.”

Adjacent to Achiampong’s own artworks at the Baltic is a gaming room, adorned with pan-African flags and filled with consoles dating from the past three decades. Intended as an answer to the standard institutional demand for an educational space, the gaming room offers a selection of the artist’s favourite games, Donkey Kong, Alex Kidd in Miracle World DX and The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask — “an amazing introduction to the power and potential of what games can do, in its sheer ability to pull you into the sublime. Simple things like running, cooking and horse riding are so beautiful and engaging.” The glorious panoramas found in “Wayfinder” and the Relic Traveller films clearly draw on Zelda. “I didn’t want to reference games without being able to play them — that would be doing what happens with a lot of subcultures when they’re invited into an arts space, they get killed off.”

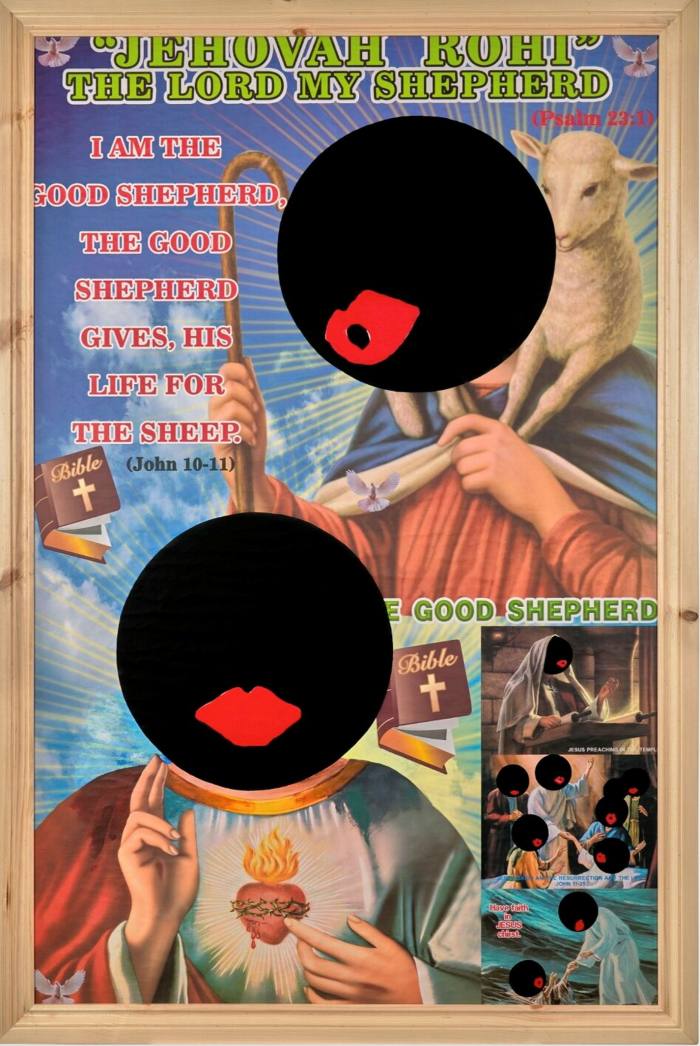

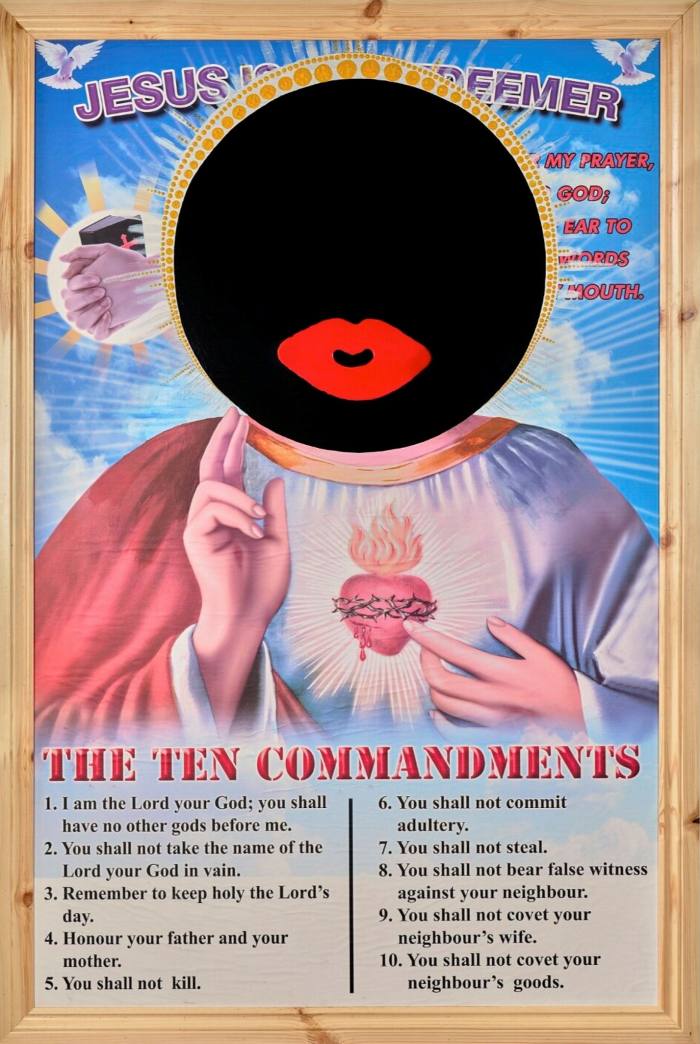

At Achiampong’s exhibition And I saw a new heaven at Copperfield in south London, there is a playable aspect too. Installed in the former church hall are four games that deal with Christianity and violence — an invitation to play, but also to contemplate the games as artworks. Side by side is a new suite of poster works that deal with Christianity’s role in colonialisation, stemming from Achiampong’s own Christian upbringing and exploration of “the mutations of my own indigenous practices at the hands of Christian imperialism”. The works are reappropriations of religious posters seen across Ghana, themselves pastiches of western adverts, with images of whitewashed biblical figures. Achiampong paints these over with black circles and exaggerated red lips, recalling minstrels and racist golly dolls — layering legacies of racism and self-erasure on top of each other.

Achiampong wants gaming to be acknowledged artistically and treated critically, contending with the idea of who can define what constitutes an artwork. Gaming is a global phenomenon and monumental industry, “but it’s bigger than money,” Achiampong urges — games can transform ways of seeing and experiencing the world. And he’s about to take this a step further: for his participation with Copperfield at Frieze London in October, he is planning the first playable art-fair booth. “I want to create a space of accessibility, in a wide sense, an environment that really allows people to jam. You have to pick up the controller.”

‘Wayfinder’ runs to October 29, baltic.art. ‘And I saw a new heaven’ runs to June 17, copperfieldgallery.com